Subscribe to ShahidulNews

By Rahnuma Ahmed

Today, 9th December 2010, is Begum Rokeya Day

We have come a long way since Begum Rokeya chaired the Bengal Women’s Education Conference in 1926, in Kolkata (Calcutta).

She began by speaking in her characteristically humorous and self-deprecating manner, although I am grateful to you for the respect that you have expressed towards me by inviting me to preside over the conference, I am forced to say that you have not made the right choice.

I have been locked up in the socially oppressive iron casket of `porda’ for all my life. I have not been able to mix very well with people, as a matter of fact, I do not even know what is expected of a chairperson, I do not know if one is supposed to laugh, or to cry.

With these opening words, Begum Rokeya launched into an incisive critique?and that too, characteristically?of the state of Muslim women’s education in colonial, and undivided, Bengal.

But before doing this, while acknowledging with all humility that the women in her audience were far better-educated than her own self, that the gathering consisted of “learned, graduate women,” she gently pointed out that her services to literature and society for the last 20-21 years, her experience of running the Sakhawat Memorial Girls School for 16 years, had provided her with the courage to speak in front of such a distinguished assembly.

To speak about women’s education means that one must necessarily talk about the social situation. This cannot be avoided, it is inevitable. And to talk about the social situation means that one must cast glances at the neglectful, indifferent and miserly behaviour which our Muslim brothers have shown towards us. That too, cannot be avoided, that too, is inevitable. We have a proverb, she said, `to speak of one’s misfortune is to cast aspersion on others.’ This, thereby, impels us to face the question, how can we give Muslim girls a good education? How do we educate them well?

Men have deceived women through the ages, said Rokeya, and women have silently suffered. Recently, however, `Sri Krishna’ has bestowed kindness on our Hindu sisters, this is why one notices signs of awakening among different Hindu communities. Women in Madras have advanced the furthest, and we now hear that a woman has been elected the deputy president of the Madras Legislative Council. We also hear that a woman has become a barrister in Rangoon. And, of course, lady Barrister Miss Ghorabji is already well-known. But what does one have to say about Muslim women, except that they continue to live in the darkness in which they have been living, for ever so long?

You will not find even 1 literate girl among 200 girls, that is the situation of Muslim women’s education. You will not find a truly educated Muslim woman, probably not even 1 in 10,000, that is the situation of Muslim women’s education; and mind you, nearly 3 crore people live in Bengal. The education department wrote me a letter last January, they needed, quickly, they said, the names and addresses of all Muslim women graduates in Bengal. But I couldn’t give them any other name than the only woman graduate we have, plus that of Agha Moidul Islam shaheb’s daughter but since Agha shaheb is not a resident of Bengal, this means that there is only 1 (Muslim) woman graduate in a population of 3 crores!!

A little later, Rokeya tucks in these lines, and this is what makes Begum Rokeya great, it is a greatness that rests on cutting-edge intellectual sharpness, is politically astute, confronts structures of power and privilege while simultaneously engaging with them, maintains a critical distance even as she works from within these institutions, and it is this, I insist, that makes her voice distinct from the `imploring’ voices which 19th-20th century Bengali women writers often adopted, or felt forced to adopt . Rokeya says, “Just as the kind-hearted British government is unable to tolerate the aspirations of the Indians?I remember, Mr Morley said 21 years ago, If they cry for the moon, it doesn’t mean we have to give in to their wishes?just as our non-Muslim neighbours generally cannot tolerate the demands of the Muslims, Muslim men too, in exactly the same manner, cannot accept the fact that women desire their advancement.” In other words, there is nothing natural about the “neglectful, indifferent and miserly behaviour” of Muslim men, they are not accidental, nor incidental for that matter, such behaviour is inextricably linked to social power and privilege, ones that are fundamental, deeply-rooted. Ones that are, in the final analysis, political, marking as they do, the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion into assemblies of the “learned” and the “educated.” Marking those who have power. Those who withhold power.

We have shown respect towards you, Begum Rokeya. The first women’s hall of residence in Dhaka university (in its early years, known as the `Oxford of the east’) was named Rokeya Hall (1964) . One of the busiest roads in Dhaka city, close to the parliament building, is named Rokeya Shoroni. The government awards Rokeya Padak each year to women who have struggled hard to contribute to the betterment of women’s lot, the government girls college in Rangpur is named Begum Rokeya College (1963), and the newly-built public university in Rangpur (2008)?the first public university in the northern region?was re-named Begum Rokeya university to honor the “legendary woman scholar who pioneered and promoted female education in Indo-Pak-Bangla subcontinent.” Social and cultural organisations too, revere you, for all that you fought and struggled for, in a life that was abruptly extinguished at 53, and of course, for the women’s movement, you are the lamp that lights our heart. Bangladesh Mohila Porishod named its safe haven for women, Rokeya Shodon, in your honor. The Department of Women and Gender Studies, Dhaka University holds Begum Rokeya Memorial Lectures on December 9th every year, and we are indebted to Rokeya Memorial Foundation, at whose initiative, Rokeya Dibosh is observed every December 9th, since 1986, the day that you were born, and the day that you left us. It would be amiss if I were not to mention our indebtedness to Abdul Kadir for having immemorialised your writings through editing the collected volume of your work Rokeya Rachanavali, (Bangla Academy, 1973). And, to Roushan Jahan too, for having edited and translated your scathing indictment of porda, Inside Seclusion: The Avarodhbasini of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (Women for Women, 1981), thereby making some of your writings available to an English-reading audience.

And since 1994, Rokeya Dibosh is observed by the government, floral wreaths are placed at your birthplace in Pairaband village in Rangpur; scores of organisations take part in discussions and cultural programmes, all over the nation, all in your honor. It is customary too, for the president and the prime minister, and the leader of the opposition, to send messages to the nation on the occasion of Rokeya Dibosh to remind us of you, of all that you fought for. In her message last year, Sheikh Hasina reminded us that if you had not shown us the path, women in present-day Bangladesh would not be working in offices, courts, mills and factories, in fields and farms, and in trade and commerce.?While Khaleda Zia, as prime minister, reminded us several years earlier that we are enjoying the “fruits” of your struggle, that it is because of you that women in Bangladesh have now become judges and barristers, have joined the army, they fly planes and work in nearly all professions by dint of their “own competence and efficiency.” She had added, if not forced to enter national-level politics to uphold the ideals of her husband, the late president Ziaur Rahman, she would have dedicated herself to building up a social movement for the emancipation of women.

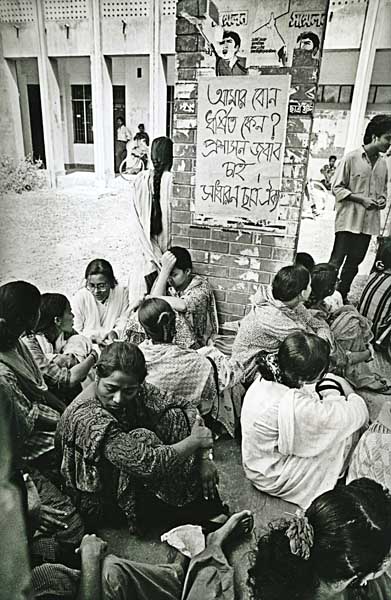

But present-day Bangladesh, according to newspaper reports, has registered a nationwide drop in the number of girls attending schools because sexual harassment and violence has horrifically escalated over the last year. Is it possible to talk about the “misfortune” that has befallen them, without “casting aspersions” on others?

On the prime minister?who reminded us in a seemingly self-congratulatory manner when awarding Rokeya Padak last year, that the prime minister, leader of the opposition, deputy leader of the house, home minister, foreign minister, agriculture minister, labour minister, and women and child affairs minister, “are all women”?because the leaders and cadres of her party’s student and youth organisations have allegedly been, in many cases, the offendors. That, to deflect public outrage, the long-discarded notion of `eve-teasing’ was re-introduced, in utter contempt of last year’s High Court verdict which ruled that any kind of physical, mental or sexual harassment?note, not `eve teasing’?of women, girls and children was a criminal offence, that the return of `eve-teasing’ served to dilute, and to de-criminalise these?offences.? That it helped create a culture of impunity which has contributed to an escalation in sexual harassment and violence, as demonstrated by the outrageous rise in figures released on International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women (November 25).

Is it possible to talk about the misfortunes of our school girls, and also, their guardians, some of whom have been killed while attempting to protect them, without casting aspersions on the leader of the opposition for leading a political party which has been galvanised into action when she was forced to leave her house, who has since preferred to desert the parliament, instead of entering it and demanding answers from the government about what concrete measures are being taking to stem sexual violence. Without casting aspersions on all who are complicit in the conspiracy of silence?sections of the media which continue to report incidents of `eve-teasing.’ Some women’s organisations which are noticeably less vocal now than when Yasmeen of Dinajpur was `eve-teased’ (raped and killed by policemen, an incident which was capitalised upon to bring down the BNP government). Will only a change of regime galvanise them into action? Into calling, for instance, a nationwide boycott of schools by girl students until effective measures have been taken by the government to ensure their safety?

Violence against girls keeps spiralling upwards: on December 4, a 17 year-old college girl in Barguna lost her leg because she spurned an `eve-teaser’ who hacked it (Daily Sun, 5 December) . And yesterday’s newspaper reports that a stalker knifed a 14 year-old madrassa girl because she refused his proposition (New Age, December 8). In both incidents, the girls and their families had lodged complaints with the local thana, but no action had been taken.

Unfortunately, Begum Rokeya, the “neglectful, indifferent and miserly behaviour” towards educating women that you spoke of enfolds us too?we, who are what we are because of you?because we are either too busy eating the fruits of your struggles, or dreaming of future fruits, or choose to remain passive, or to play it safe. You were right to remind us that education is not only about acquiring degrees and certificates, that unless a qualitative change in the state of one’s mind has occurred, we remain murkho, we remain enslaved..

And today Begum Rokeya, we, both men and women of this country, will provide ample evidence of that. Flowery words will escape many a lips, all in your honor.

As you shudder in your grave.

Published in New Age, Thursday December 9, 2010