Tag: painting

DAVID HOCKNEY?S CUBIST PHOTOGRAPHY

Source: Dangerous Minds

?I had become very, very aware of this frozen moment that was very unreal to me. The photographs didn?t really have life in the way a drawing or painting did, and I realized it couldn?t because of what it is. Continue reading “DAVID HOCKNEY?S CUBIST PHOTOGRAPHY”

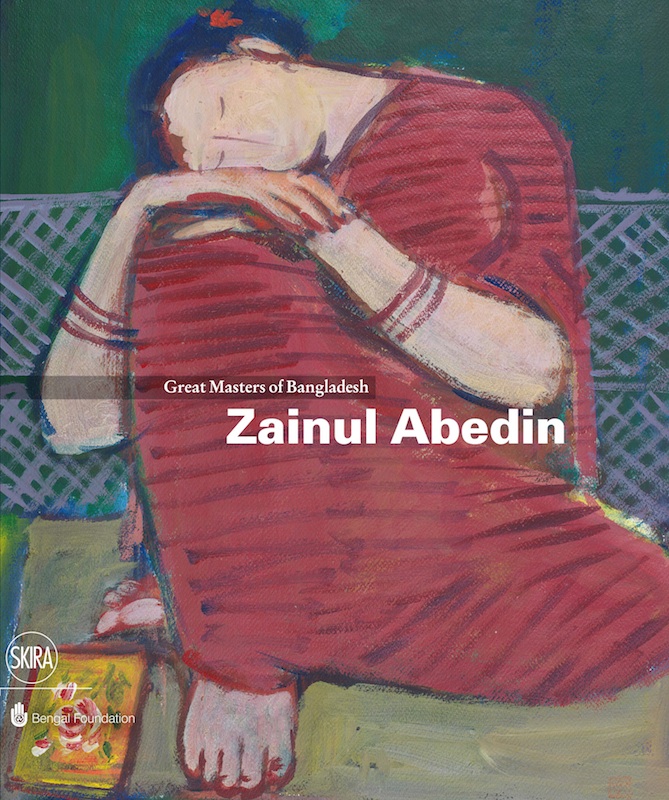

Zainul Abedin

?What gives me even more joy than creating my own artworks is seeing art being nurtured?in?society…Art should be turned into an all-pervasive, daily practice.” Zainul Abedin

The only comprehensive survey of?Zainul?Abedin?s work to date and the second volume?in?a?world first series dedicated to the ?Great Master Artists of Bangladesh?, edited by Rosa Maria Falvo, co-published by Skira?inMilan and the Bengal Foundation?in?Dhaka.?Zainul?Abedin?(1914-1976), reverently called the?Shilpacharya?or ?guru of art?, is the architect of the modern art movement?in?Bangladesh, which began with the setting up of the first Government Art Institute?in?Dhaka?in?1948. For his devotion to art education and his visionary and artistic achievements?Abedin?has always been the undisputed protagonist of the Bangladeshi modern art scene. With essays by Abul Monsur, Nazrul Islam, and Abul Hasnat, this book showcases?Zainul?Abedin?s work over?aperiod of 40 years, with more than 200 colour and black and white plates illustrating his special relationship with his country, from various artistic, social, and political perspectives. This beautiful and ground-breaking volume retraces his personal vision and provides the best interpretative angles into?a?culture and reality that has often been overlooked and even misunderstood?in?the West.?Abedin?s humanitarian stance and his commitment to art forged the way for an entire generation of Bangladeshi contemporary artists. Continue reading “Zainul Abedin”

The 3rd International Resistance Art Festival

Dear Artist;

We are pleased to inform you that Visual Arts Association of Islamic Revolution and Holly Defense in Iran is about to hold ?The 3rd International Resistance Art Festival? in November 2013. The Festival is held in 12 categories including Painting, Drawing and Printmaking, Persian Painting, Calligraphic Painting and Typography, Illustration (Graphics), Poster, Photography, Caricature and Cartoons, Sculpture, Animation, New Conceptual Arts and finally, Scientific Congress and Research Papers. Please read the entry information below. If you are interested to participate, please attach the images of your works to this email based upon the conditions that mentioned below. (For the primary selection, only the images of your works are needed). It is notable that you can participate in more than one category in the festival contest.

WE WILL WELCOME THE SUGGESTIONS FOR CREATIVE AND NEW PROJECTS. Continue reading “The 3rd International Resistance Art Festival”

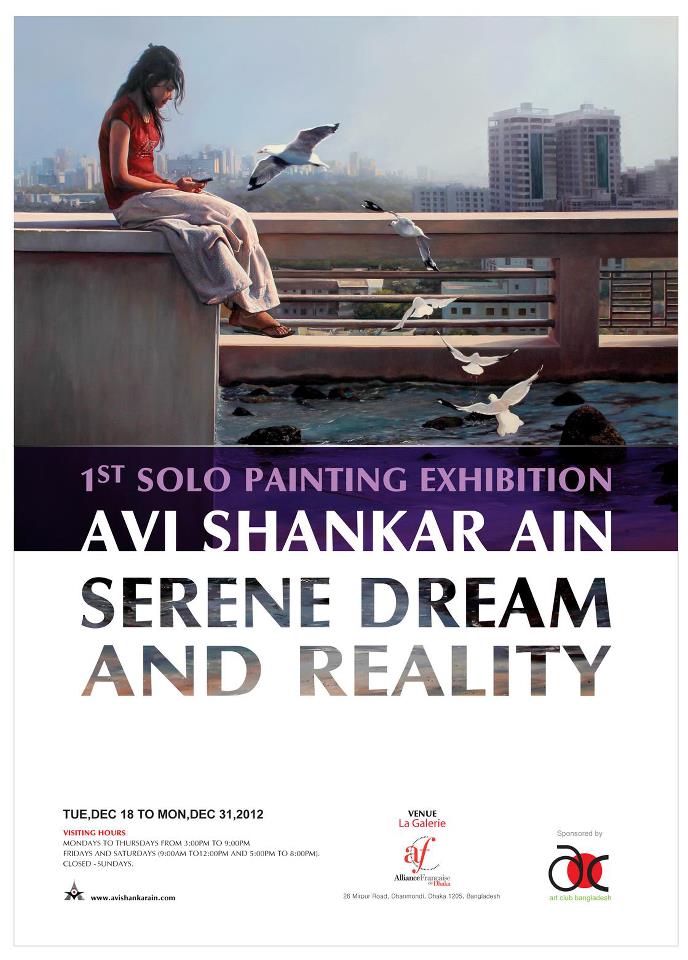

Serene Dream and Reality

1st solo painting exhibition of young artist Avi Shankar Ain

Avi’s father, artist Ravi Shankar Ain, has been doing the calligraphy for Drik’s calendars for the last twenty years. Continue reading “Serene Dream and Reality”

Explore. Dream. Discover

by?Sanita Ahmed

New Age

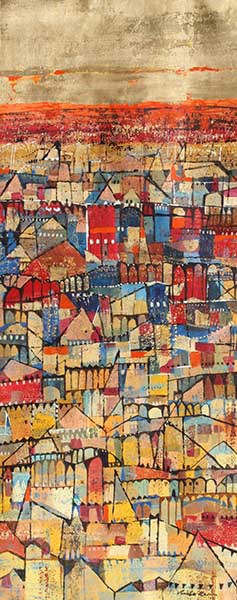

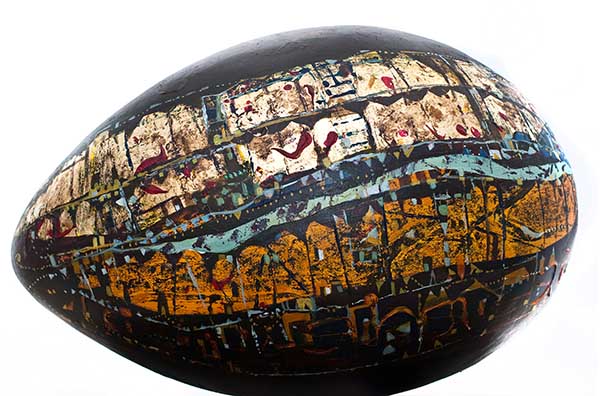

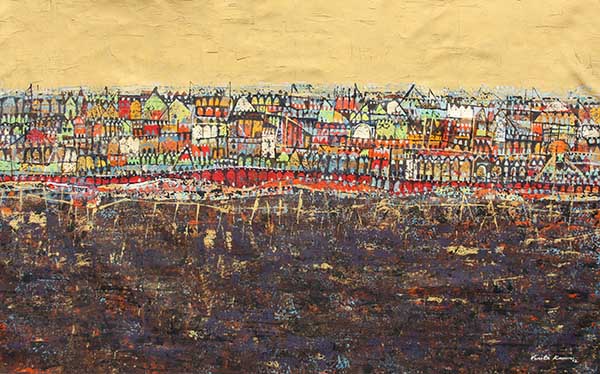

If the world has an ovarian shape and nobody knows when it really ends, then Vinita Karim?s artistic endeavours seems to be ongoing on a cyclic loop of intriguing artwork exhibits. The artist?s latest exposition opened at the Bengal Art Lounge on October 13, where Chief Guest, Pankaj Saran, the High Commissioner of India to Bangladesh inaugurated the exhibition. The title echoes the feel of the exhibit, where Vinita reintroduces her artworks from the last two decades as the artistic extraordinaire she is at creating natural worlds through symbolic paintings.

The gallery showcases the distinctive forms of Vinita?s creations over the years, from the acrylic paintings collided with a rich harmony of vibrant colours from 1995 to the unconventional ovoid shapes she created in 2011 by mulling them over with lustrous landscapes.? Vinita?s paintings are not constructed exclusively from the inspiration of landscapes; rather she implements her intricate acrylic techniques to conjure up a beautiful composition using certain elements that can be found in such landscapes.

The occasional boats, the blossoming waterbeds and the rural skyline are repetitive components of her paintings which are formed with contoured brush strokes in an asymmetrical grid-like fashion. The arbitrary placement of such elements works up a fury of abstraction and along with the impressionist scenes, Vinita?s paintings blend the structural realm of colour and random natural ingredients in one astounding kaleidoscopic vision.

She also draws inspiration from 20th century Austrian artist, Friedensreich Hunderrwasser who creates his landscape paintings using similar styles. Although she was born in India, she is marinated from the rest of the world, a result evident in her paintings where she has injected her experiences from India, Switzerland, Egypt and Philippines.

She first started creating ovoid installations when she was living in the Philippines. A tornado had caused an abundance of trees to collapse, from where Vinita collected the branches and created her first oval structure using wood. Now, she creates the same using fibre glass and she explains her affection for the oval shape since it symbolizes the birth of creation.

Most of her paintings and installations are layered with deeper significances where she weaves geometric and fluid forms and creates a mythical vortex of her perception of home that makes the viewers fall in the depths of a naturalistic empire where emotions all collide into one big supernova that envelops the mind with an encompassing grasp. Being an exhilarant wanderer, she believes home is not restricted to a singular place and over the years, her paintings have matured into a natural dominion of her inner space.

The exhibition hosts the artistic evolution of Vinita over the last twenty years where viewers are brought out of the normative gaze and sprung face-to-face with a majestic set of artwork that are more than just landscapes but rather, a visual extension of the artist?s imagination and creativity. This is the artist?s third exhibition in Bangladesh since 1995 and 1998 and she hopes to re-introduce her paintings in the local art scene in Dhaka. The exhibition will remain open until October 25.

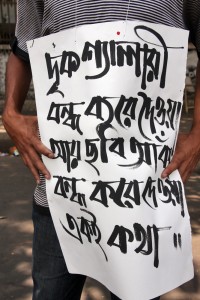

Drik: Photo power

By Satish Sharma

The shutting-down of two photographic exhibitions in Dhaka?s Drik Gallery in just the last few months proves that Bangladesh?s censors, unlike lightning, can strike at the same place more than once ? especially where Drik?s photographic practices are concerned. But then, Drik seems to have become a lightning rod inviting censure, and this will not be the last time either. Not if I know Shahidul Alam and his commitment to pushing photography in what he calls ?the majority world?. If actually being knifed has not stopped him, nothing will.

The British Council in Dhaka had once tried to shut down a Drik exhibition by Roshini Kampadoo because it ?hurt the image of Britain?. And in November last year it was the turn of the Chinese embassy in Dhaka that wanted an exhibition on Tibet, also in Drik, to be closed. When a personal visit by the Chinese Cultural Counsellor and his cultural attach? bearing gifts (calendar, a silk tie and tea) didn?t work, they invoked worsening diplomatic relations and brought to bear the weight of the Bangladeshi government, Special Branch police and even parliamentarians. But Alam didn?t buckle, instead inaugurating the exhibition in the street after the gallery was locked up by the police. He shut it down the next day, however, as a protest against the interference.

Alam?s new exhibition and installation, ?Crossfire?, should have been safer from threats of closure. It was not photojournalistic documentary or even an Americanised ?documentary style?. It showed no dead or disappeared people. Much more conceptual, it allegorically invoked the disappeared through subtler and quieter means. But because it dealt with ?crossfire? deaths by specially raised Rapid Action Battalions (in India, one would call these ?encounter deaths?), it drew fire ? and closure, and protests against the closure.

There is something about photography that invites censorship. The power of the photographic image simply has to be controlled, it seems ? one way or another. If ideas of aesthetics, beauty and spiritual values don?t work, governments pass and use anti-terror laws. And internationally applicable anti-terror laws, with the attendant globalised cultural control, are now beginning to have a universal presence, reach and influence.

Any critical photography is subtly suppressed by evoking ideas of photography as a ?fine art?, and by inducing self-censorship before it is more pointedly and politically policed through action by the state?s security services. Self-censorship, I believe, was at the heart of the lack of any decent coverage, by Indian photographers, of the Emergency and the 1984 anti-Sikh riots.

The desire to control the photographic message is, however, universal. And that desire is as old as the medium itself. From colonial control of the photography during the 19th century to anti-terror laws in the era of the global ?war on terror? to control the photographic images of the 21st century, little seems to have changed. The power of photography to control and manipulate perception of the world?s raw realities is too important to be left unchallenged. It is noteworthy that these do not even have to be powers from one?s own country. Perception management is a global political strategy with a global reach; it is globally practiced.

In February, Uzbekistan convicted a photographer for ?slandering the Nation?. Umida Akhmeddova had been documenting the daily struggles of ordinary people, and was accused of ?portraying the people as backward and poor?. Her ?photo album [did] not conform to aesthetic demands? and ?would damage Uzbekistan?s spiritual values?, said the expert panel appointed to look at her work.

The Abu Ghraib photos were not shot by professional photojournalists, yet special laws were passed by the US Congress to prevent their dissemination. Most of the pictures and video footage still remain out of reach ? legally secured, not only by the special acts of the US Congress, but also through the raising of issues such as the right to privacy of the ?victims? and their oppressors, and by wives of the soldier-photographers who raised issues of personal copyright to prevent these photographs from being seen more widely.

Anti-terrorism laws are also being used to prevent photography in Britain?s streets. Photographing the most well-known monuments has become suspect, with even professional press photographers being harassed by local police. Street photography, we have to remember, has a long and proud tradition, and the streets have a central space in the practice of urban photography. Even photography as a safely sanitised art form, a documentary style, is not a safe practice. But then, safety is not what should drive photography. It needs to recover and secure its critical spaces ? its critical power.

Satish Sharma is a photographer, critic and occasional curator. He was a former tutor at Pathshala and currently lives in Kathmandu.

The article was published in Himal Southasian

Related links:

Sri Lanka Guardian

Earlier post on Crossfire

Painting and Photography

The Golam Kasem Lecture Series

By: Dhali Al Mamoon

6th September 2009. Drik Gallery Dhaka

Painting and Photography

Dhali Al Mamoon

Is there an art form that does not draw upon other disciplines? Are literature, music and architecture not informed by visual culture? Are the many manifestations of visual art not encapsulated within them? Today, the boundaries of creative work are difficult to define. If one has to draw a boundary, perhaps it is the sky. The activities that question our intellect, philosophy, science or art ? have all directly or indirectly, become complementary.

Painting and photography, these two forms of visual art are about seeing and showing, creating images and visual signs. The differences in their mode of production, has created some particularities. Painting is not merely the earliest form of visual art, but also the earliest example of human creativity. In this long journey, its structure, its form, its language and its expression both outside and within, have drawn upon each other and gone through transformations. Photography, the youngest of the visual art forms, is less than two centuries old, but has gone through dramatic shifts both within and outside.

The advent of this young visual art form has influenced painting, the earliest visual art form, the most. Very few painters have been able to distance themselves from this influence. According to many, photography has evolved from within the fine arts. Painters have searched for ways to capture the fleeting visuals that surround them, and it is this need that has enabled the discovery of photography.

Earlier in this decade the celebrated British painter David Hockney through his book, ?Secret Knowledge? analysed the creative practices of prominent western artists. This led to a storm of controversy in learned circles, for in that book, Hockney talks of how, well known artists had, prior to photography, used various techniques to enhance their painting skills. Da Vinci, Vel?zquez, Caravaggio, Van Eyke and many other painters had used lenses, mirrors and many other optical devices, to help them create their paintings. The book provides detailed descriptions of these techniques.

One of these devices was the camera obscura. Astronomers had used the camera obscura to obs as early as erve heavenly objects1630. This led physicists and optical scientists to the invention of the telescope and the microscope which revolutionized astronomy and the world of unseen microscopic objects. It opened up a new frontier in our visual culture.

The camera obscura took on many shapes and forms between the 16th and 19th centuries. Large, small, with and without lenses, with reversing mirrors, etc. They were all designed to render a faithful rendering of the scene before us.

Of those who were involved with painting and the visual arts, and also played an important role in the development of photography, a key figure was Louis-Jacques-Mand? Daguerre. Well before he began to improve upon the camera obscura he had established a reputation as a painter, particularly in panoramic painting and theatrical illusion. He later invented the diorama. He began experimenting with photography since 1823. Meanwhile another artist, Joseph Nic?phore Ni?pce successfully created a permanent rendering of a scene in 1822. Ni?pce had been working on lithographs for quite some time. So the advent of photography involved an amalgam of the two disciplines right from the start. Daguerre and Ni?pce began collaborating on their research, and overcame many of the obstacles in their path. In 1833, after the death of Ni?pce, his son succeded him as Daguerre?s partner.

Daguerre?s successful use of photography in 1839 (by a process known as the Daguerreotype) when he was able to record the effect of sunlight through chemical means, created a stir, and the Parisians felt this was superior to painting as it was more lifelike than painting could ever be. The Daguerreotype became increasingly popular and the use and power of photography spread. At the same time, Daguerre was given more responsibility, particularly in the preservation of valuable documents.

By the time photography became ubiquitous in the representation of human activity, the human landscape had also begun to change. Industrialisation led to the disappearance of earlier modes of living. Perhaps the camera too is a product of this industrialization. Photography?s ability for accurate representation led to a rapid increase in its usage. Since the Paris Commune, photography began to be used as material evidence in many political investigations. The revolutionary transformation that had taken place in advertising, post-Napoleon, due to the lithograph, was succeeded by a similar transformation due to photography. The role played by painting was gradually taken over by photography. Gradually, photography took on a more diverse role. Its contribution in extending the scope of visual arts to that of visual culture, is well recognized. On the other hand its replicability gave the image a popularity which other visual art forms like painting lacked due to the limitations of the medium. Rather, even in the fine art spectrum, the reproduction of paintings through photography has led to its democratization and a place in popular culture. Other artwork in museums, galleries and private collections, have become more accessible to the general public by their reproduction through photographs. Consequently, the chapters in western contemporary arts that have gained in prominence, owe their success to the discovery of photography. The advent of photography has transformed the structure of painting, its language, its technique and its perception. In adapting an image or painting to the confines of the photographic process there are elements that get truncated. Before the advent of the mechanical eye of the camera painters were very conscious of these truncations and ensured that the canvas was able to contain the gaze of the viewer. Visual boundaries were created through the use of shadows, or play of colour to restrain the eye. However, dividing the canvas itself was deemed acceptable. The image is a fragment of the visual scene, but artists want to create a complete vision, through the conjunction of images split across canvas divides. The tensions between the whole and the fragment, the seen and the unseen reflect the effects of the artist and the perceptive influences of the social structures she finds herself in. The visual structure or composition of an image has a focal point, around which the other elements are placed. This placement could even be an invisible pyramidal structure that provides stability in our everchanging reality. An attempt to arrest time, or perhaps suggest timelessness. The ramifications of the contemporary art forms reflect perhaps current social structures, and our collective wisdom, religion, philosophy, concerns, from the deeply personal to the centralization of power.

Our perceptions are changing. The inventions, the tools, the techniques follow a parallel path to these ideas. Photography is such a representation of our times. This avatar of our times has broken the boundaries of our experience, it has immersed itself into the fine arts. Similarly, this advent of photography has injected new energy into other contemporary fields of learning. The visual divides of a canvas are no longer a threat to the painter, rather she has learnt to incorporate it into her visual language. Her frame can now be invaded by peripheral objects that interject, exude, linger at the edges. The snapshot aesthetic has been appropriated into her language. What is interesting is that such visual grammar was in use even before photography was invented. Perhaps this was a pre-visualisation of photographic forms in our minds. It manifests itself in woodcuts. Perhaps the impressionists were inspired by Japanese printmakers in the same way that the visual truncation of photography has influenced other visual artists.

In the early days, photography was perceived as a threat by painters, but instead they have gained a new independence and a different visual grammar. It was the impressionists that led the way to this change. The aspects of photography that were trapped within the accepted norms of painting have also found new freedoms. The techniques of dissemination, as well as the specificities of production have become modes of expression for the artist. Freed of the rigidities of material taboos, there is a new democratization in the arts. The modes of production have opened new doors. There was a time when artists followed pre-determined layouts or set ideas which were enacted in the studio. Now they migrate to the open, letting their experiences guide their artistic rendering. No longer does their art work need to conform to a fixed visual straightjacket. The acceptance of this uncertainty has been liberating. The edges are now blurred. The brush has taken on new forms. The ability to freeze fleeting moments, has led to time and timelessness becoming elements of construction. The appropriation of photography has led to a modernization of the arts.

Photography has become a vital ingredient not only of visual arts, but of visual culture. But art critics and intellectuals have raised questions about the creativity and aesthetic validity of the medium. However it was in 1859 when photography held its own space in the Paris Annual Art Exhibition. A few years later in 1863, after a few legal skirmishes, photography was officially recognized as an art form by the French government.

While painting has been influenced by photography through seen and unseen ways, photography too has gained through the discipline of the visual arts. The pictorial syntax of painting has evolved over time. Many consider photography to have a ?pictorial syntax without a syntax?. There are others who think photography is a literal rendering rather than a representation of reality. That it is a receptacle for reality, and can hold no more than what is visually obvious. That it does not have the independence that other visual art forms have. These questions about the validity of photography as an art form have now lost relevance. What a photograph holds depends upon who, when, where and how, it is presented and contextualised. The postscript film ?Letter to Jane? (1972) directed by Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, is a back-and-forth narration by both Godard and Gorin. The Hollywood actress Jane Fonda had gone to Hanoi during the Vietnam war. A photo of her was printed in the French newspaper L?Express. The film serves as a 52-minute cinematic essay that deconstructs the single news photograph.

It is difficult to value a medium based on its specific characteristics. It depends upon time, space and context, and the perceptions of the individuals or collectives that surround it. It is true, that photography can seek out, hold, capture and select, or arrange. While it may differ in modes of creative production, are these not intrinsic to all other art forms? In practice these categorizations depend upon the depth of intellectual ability, the sensitivity, the passion, and even the knowledge of the one who decides. That is precisely why creative work varies with time, space and context. Marcel Duchamp?s ?Fountain?, opened up new spaces for creativity. Soon the tools, the medium and the process, of art became secondary, the ideas and the concepts became the central elements. Duchamp inverted a urinal and called it art. He established the relationship with the roots of one?s work with what one created. He linked creativity with history and culture. His notion that art could be about ideas rather than material things revolutionised thinking about art. When this urinal, through its presentation lost its original functionality, then it entered a new space. Took on new meanings. So the construction of the artwork, or the creativity in its form gave way to the ideas and concepts of the artist.

The interrelationship between painting and photography in Bangladesh is different. In our visual practice, the fine arts institute has a firm foundation. From an organizational perspective it is this academy which quantifies artistic merit. As I?ve mentioned earlier, the Salon de Paris had, over 150 years ago, accepted photography as an art form in fine art exhibitions. That is about a 100 years before fine art practice itself was initiated in Bangladesh. We suffer from the inferior complex that colonial heritage has left us. We unthinkingly accept what is western as superior, so why this condescending attitude towards photography? Even now the fine art exhibitions at Shilpakala Academy (the academy of fine and performing arts), do not recognize photography. But the funny thing is that at the Asian Biennale, many participating countries submit photography as their artwork. More recently digitally manipulated photography is accepted as art. So even the disparity towards the medium is not consistent. Why then is photography not treated as part of the visual arts in Bangladesh?

This may be due to the patriarchal mindset or the fundamentalist concepts about fine art or to do with the power-play between the strong and the weak, the experienced and the inexperienced, or indeed a struggle between the past and the present, the old and the new. We have not learnt from the natural progression of either history or civilization, where progress is entwined with change. Who knows where our art is heading? Our lifestyle, or reality, or work sphere, our learning, our future, our hopes and the dreams of our next generation will shape the future of our art.

Translation by: Shahidul Alam

Dhali Al Mamoon

Dhali Al-Mamoon is a painter and a lecturer at Chittagong University. He was born in 1958, in Chandpur, Bangladesh. He holds a Master’s Degree in Fine Arts, University of Chittagong. He received the National Award 2000, Shilpakala Academy, Dhaka, for the best art work of the year and the Grand Prize in the 12th Asian Art Biennale, Dhaka, 2006

The present as history. Life and death in Dilara Begum Jolly's work.

by Rahnuma Ahmed

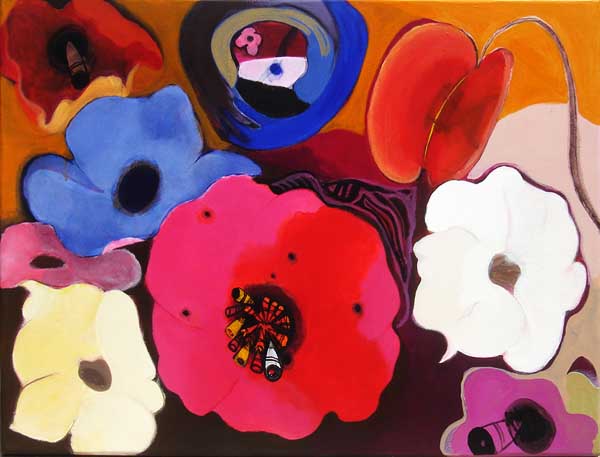

Flowers blossom, but with bullets in place of stigma. Bullets signal the end of fertility, the end of life. They signal death and destruction (After the end of time – 3).

A chess board. The king wears Stars and Stripes, his minister is dressed in the Union Jack. Soldiers litter the board, two have holes in their hearts. The path to a target practising board is strewn with eyes, un-seeing eyes. Dead targets. One eye, may be half-alive, stares at us unblinkingly. An eagle, hovering above, stops in its flight of extending the empire, to oversee American-style democracy take root in a faraway land (Before the end of time – 2). This is how Bangladeshi artist Dilara Begum Jolly captures the present moment on her canvas.

Bodies fractured by wars of the present, dismembered limbs, single hands — coloured red, yellow, blue, purple — lie lifeless. Others are raised upwards, they seem to be imploring. Stop this madness, stop the war. A human body folded, her head and pair of legs buried beneath the soil, her arms too. The trunk of her body and her fingers are visible. Fingertips stretched outward, towards the sun, towards light. A flaming red petal of a bird of paradise springs forth like a knife from the navel of a human body as she lies face upwards, her hands tied in a knot. A pair of army boots remind us of how it happened (Before the end of time – 4).

An Iraqi flag interweaves between dead bodies lying in a heap. Mother Teresa grieves silently as a furious red hand, gloved in Stars and Stripes, hangs over — and above — everything else. Once again, a Union Jack, this time in the background (Before the end of time – 1).

Other canvases, other images. Naked bodies, imprisoned bodies heaped on each other, surveilled by an eagle eye, the new owners of Abu Ghuraib. Autumn leaves falling on a white background as women, dressed in hijab, some in brown, others in purple, or blue, grey, white, stand shoulder to shoulder to the right of the canvas. They seem to be grieving. May be for a lost husband or a daughter. May be a son, a grandmother or a lover. For people, obscured by words spun by the invader — safe and secure in Pentagon, Washington, Fort Benning, and Downing Street — “collateral damage.” May be for the loss of national independence and freedom.

Other canvases, other images. Not any civilisation, but the cradle of civilisation itself destroyed. Army vehicles advancing on monuments. Statues and sculptures lying scattered as blank pages of history waft down. A Buddha head looks impassively as a shot is fired into its right eye. A broken cuneiform tablet.

And yet, in the midst of all the death, destruction and havoc, a pink lotus blooms. And that, as we who are familiar with the artist’s work know, is Dilara Begum Jolly’s signature. A flower, a sapling, a shoot springing forth in the midst of ruins. Signalling life, its force and energy. Its beauty. Signalling the will to live. The death of forces of evil.

Dilara Begum, known more by her nickname Jolly than her proper name, has always produced art that is social, and political. That is keenly critical of the prevailing order, whether at home or abroad. Or, as her exhibition Excavating Time (Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts, 4 – 17 September 2006) shows, of the new order that has not only destroyed the cradle of civilisation, but threatens to destroy all vestiges of life on the planet. An inexorable war machine, spinning lies and deceit to the heavy rounds of applause by western politicians, generals, defence analysts and journalists.

Other canvases in the exhibition drew on the womb, on foetuses, on the pain of giving birth. Or, of not giving birth, of an embryo that retreats into the womb, repelled by the patriarchal order that controls and regulates life outside (Embryo withdrawn – 1).

Jolly’s more recent work draws on the the nokshi kantha (quilt-making) tradition of Bangladeshi women, quilts that are made from worn-out saris, two to three sewn together, richly embroidered from folk tales, myths, everyday artefacts, and daily village life as seen by, and as intrepreted by, women. Always. Instead of strokes and brushes, Jolly paints short stitches that weave tales, of women as mothers, as sisters, and as friends, drawing on traditions of weaving to tell stories of the pain and wonderment of giving birth. Of creating, and re-creating, bonds of solidarity.