Press release

German Foreign Office and Neue Galerie Berlin will present Shahidul Alam at Deutsche Welle?s Global Media Forum and at the Global Forum on Migration and Development in Berlin.

With the book publication and the exhibition ?The best years of my life. Bangladeshi Migrants in Malaysia? the international well-known photographer and activist Shahidul Alam will be present on Monday, June 19, 2017 through the Neue Galerie Berlin and with the support of the German Foreign Office on the Global Media Forum of the Deutsche Welle. After the end of the forum in Bonn, the exhibition will be on display at the German Foreign Office in Berlin from Thursday, June 23, 2017, and will be part of the Global Forum on Migration and Development from 28 to 30 June. The Finissage will be published on 30 June 2017 at the Federal Foreign Office with a greeting from the State Secretary Dr. Markus Ederer within the framework of the GFMD. The artist will be present in Bonn and Berlin and will be available for questions and interviews. Further information on the exhibition and the artist in the appendix.

As an additional digital component, the Neue Galerie Berlin, together with the technology partner snap2live, presents the newly developed image recognition app ?Neue Galerie Berlin?. All pictures of the Alam exhibition can be scanned with the app (tentatively available on Android). Behind the pictures

About

In 2016 Tanja von Unger founded the Neue Galerie Berlin (www.neuegalerieberlin.de).

To provide a relevant platform beyond photography the businessmodel

also collaborates with publishing groups and institutions and is known for its groundbreaking presentation of photographers and their works at economic conferences and events such as the Economic Summit of the Su?ddeutsche Zeitung, Falling Walls Conference, Rheingauer Economic Forum, Global Solutions G 20 Conference of the Dieter von Holtzbrinck publishers.

Snap2Life create apps for companies in the media, publishing, automotive, business, sports and advertising sectors. Most of these apps are equipped with our innovative image recognition functionality, which we also provide as an API for integration into other apps. In a fraction of seconds we connect the offline world with any kind of relevant content from the online world.

The Deutsche Welle Global Media Forum (GMF) is the Place Made for Minds, where decision makers and influencers from all over the world come together. It?s the global platform put on by Deutsche Welle and its partners and the place where you can connect and strengthen relations with over 2,000 inspiring representatives from the fields of journalism, digital media, politics, culture, business, development, academia and civil society. The conference provides a unique opportunity to network, get inspired and collaborate using a wide variety of state-of-the-art formats.

http://www.dw.com/en/global-media-forum/global-media-forum/s-101219

?Towards a Global Social Contract on Migration and Development?

Tenth Global Forum on Migration and Development Summit 28 to 30 June 2017, Berlin

Germany and Morocco have assumed the co-chairmanship of the Global Forum on Migration and Development (GFMD) from 1 January 2017 until 31 December 2018. During this two-year period, the focus will be on the contribution of the GFMD to the United Nations? Global Compact on Migration. The Compact is intended to constitute a strong signal of the international community for an enhanced global migration policy, to be adopted by the community of states in 2018.

https://gfmd.org

Tag: labour

Dhanmondi Brickbreakers on Vimeo

Dhanmondi Brickbreakers on Vimeo

The traditional form of brick breaking has now been replaced by machines that do the bulk of the job. As with most low paid jobs in Bangladesh, there are many associated risks.

Update on Mishu's health

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

Dear friends,

Hello, I’m sorry for not having sent my regular updates for the last two days, caused by writing deadlines.

Moshrefa Mishu’s health has worsened. Her back pain from a spinal injury has increased. She has constant fever, her heart palpitation has increased and medicine, her youngest sister tells me, is not alleviating her condition.

Police who keep her under close watch have begun behaving very badly with her family members and her organisation’s colleagues. Since Friday afternoon, 24 December 2010, they have begun shouting and using abusive language. Only one attendant is permitted to sit beside her, no one else, not even her sisters are allowed to approach her bed, or to speak with her, whether in person, or over the mobile phone.

We are deeply alarmed, both at her worsened health while in hospital, while receiving medical care and attention, and at the changed behaviour of the police on duty, overtly aggressive and abusive, that too, towards a person who has been hospitalised, that too, in a woman’s ward in a government hospital where there are other patients, most of them severely ill, since hospital authorities generally discharge a patient as s/he improves due to scarce resources and pressure for beds, medical attention and treatment.

Left political alliances held protest rallies on Friday, December 24, 2010 in front of the National Press Club, Dhaka, demanding the immediate release of Moshrefa Mishu, and Bahrane Sultan Bahar, president, Jago Bangladesh Garment Workers’ Federation. Speakers said, arresting labour leaders would not contain labour unrest, acceding to living wages and trade union rights would.

Letters of solidarity have been pouring in from both organisations and groups committed to workers rights, and individuals, both at home and abroad who are aghast and angry at the government’s repression of workers and their leaders, who are struggling hard for a bare minimum.

Please keep passing the message around, and also, pls fwd the online petition as widely as you can.

http://www.gopetition.com/petition/41542.html#fbbox

ONLINE PETITION Free Moshrefa Mishu and all detained workers immediately!

In solidarity/rahnuma

LIVING WAGES FOR GARMENT WORKERS

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Moshrefa Mishu,?illegally arrested and remanded.

By Rahnuma Ahmed

I have known Moshrefa Mishu for the last 25 years.

Since the mid-1980s when the two of us had participated in long and intense discussions with other representatives of both large womens organisations and small womens groups, when we were trying to work out the possibility of forming a broad-based and united platform to collectively struggle and further the interests of women.

In the early hours of 14 December 2010, Mishu, who is the president of Garment Workers Unity Forum, was picked up from her house in Kola Bagan, Dhaka, by a contingent of a dozen or so in plainclothes (excepting one). They claimed to belong to the Detective Branch. They did not have an arrest warrant. Please remember that, as you read along.

She was produced in the Chief Metropolitan Magistrate’s (CMM) court after midday. Police sought a 10-day remand, the magistrate granted 2 days. She was accused of inciting garment workers at Kuril who were, according to news reports, demonstrating for payment of wages according to the new pay scale agreed upon by the government and factory-owners in August 2011. Demonstrating for, not against, and mind you, the government was a party to the agreement. Does it not strike you as strange that workers should have to demonstrate and picket, and to press for demands which are in effect, also the government’s demands? (workers had unwillingly agreed to the new wages because it fell far short of their demand for 5,000 taka as minimum wage, not the 3,000 taka which was agreed upon, which has been termed `poverty wages’). Workers at Kuril alleged that the management was not following the new wage board, it had added only 500 taka to each worker’s wage. Remember Kuril too, because I’ll come back to this later. Instead of imprisoning garment workers and their leaders, one would have thought government officials and factory-owners would be arrested for not complying with the wage board’s settlement.

She was remanded again, for 1 day, on December 17. The police added another allegation to their previous list, Mishu had been seen in the company of a Jamaat leader, travelling in his car. Where? When? Not surprisingly, the police could not substantiate their allegations, they could only insist that it needed to be investigated.

Mishu was produced in CMM court for the third time on December 19, afternoon. I was among a group of activists (university teachers, writers and a lawyer) who had gone there to express our moral support for Mishu. Only Sadia Arman among us was allowed to enter the courtroom as she’s a lawyer. She spoke to Mishu who sat in a bench at the back, with women police on either side. She was breathing with great difficulty, gasping for air as she spoke. She told Sadia that short of beating her, the DB police had tortured her in every possible manner. When Sadia asked her about the allegations against her, Mishu said, she had not been in Kuril but in Narsingdi, she had returned to Dhaka on 12th night, had been exhausted and had declined to attend programmes till December 16. She did not know why she had been arrested, they had not told her anything. Please note that the protests at Kuril occurred on 12th morning and that the allegations against her are not, according to the laws of the land, worthy of a remand.

We caught a glimpse of Mishu as she left the courtroom heavily surrounded by police. I watched a young policewoman flash a smile as she said confidently, oh, there’s nothing wrong with her. She’s fine. As we turned the corner of the courtroom and stood above on the landing, we watched Mishu climb down the stairs assisted by policewomen. We could clearly see that she was unable to walk by herself. I remembered an Indian feminist friend’s excitement when Sheikh Hasina appointed Sahara Khatun as the minister for home affairs. I had not been similarly excited. The proof of the pudding is in the eating, I thought.

Mishu’s breathing difficulties increased, she had to be hospitalised immediately. She was taken to the National Hospital first, where the doctors gave her a nebuliser and oxygen. Her back pain — from a spinal injury, the result of an attempt on her life several years ago which had been staged to appear as a road accident — increased tremendously. While she had entered the hospital sitting in a wheelchair, she had to be carried out on a stretcher. She was referred to the Post Graduate hospital where doctors provided further oxygen, she was then referred to the Dhaka Medical College Hospital. She lies in a `bed’ there, in a womens ward, hastily put together on the floor, as there were no vacant beds. Police surround her bed, both men and women, causing immense distress and embarassment to both Mishu and other patients, many of whom are confined to their bed and having to use bedpans for urinary and fecal discharges.

What induced this? Mishu was without medicine for more than 24 hours, the contingent who had gone to pick her up had only permitted her to change her clothes. Despite being a chronic asthma patient, she was forced to lie on the cold floor of the DB Headquarters with only a thin blanket to lie on, and a thin quilt as cover. By the time her sister was allowed to drop her medicine at DB Headquarters, she was already very ill,

the nebuliser was unable to provide any relief. She would have preferred a prison, she told her sister, as she would at least have some hours to herself, at the DB HQ she was interrogated at all odd hours, both during the day and at night.

What is equally worrying is that officials at the DB headquarters had told her sister before the court hearing on December 19, don’t worry, we’ll provide her with some hot water tomorrow so that she can take a bath. How could they have been so sure that their prayer for a remand would be granted? Is unseen pressure being applied by the government on the judicial process?

A garment worker had explained to a Reuters correspondent that the reason for protesting was “because [the new wages are] too inadequate to make ends meet. We cannot submit to the [whims] of the government and factory owners.” Another had said, “We work to survive but….commodity prices are going up and we cannot even arrange basic needs with our meagre income. The 3,000 taka will be barely enough to buy food for my six-member family. How can I pay for medicines, the education of my children and other needs?” Nurul Kabir, the editor of this paper, in a talk show on a private TV channel the night Mishu was arrested, had said, he would like to give factory owners Tk 3,000 per month, for a period of three months, and would like to see how they managed to live on this meagre amount. I agree with him, I think such an exercise, conducted publicly, with daily updates, would prove to be tremendously educational.

Or, one could reverse what the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, imprisoned from 1926-1937 (the prosecutor had said at his trial “for 20 years we must stop this brain from functioning”), had written to a family member, from prison: “tell me what the following categories of people eat in a week: a family of,

- day labourers

- sharecroppers

- small farmers who work their own land

- shepherds whose flocks are a full-time occupation

- craftsmen (cobblers or blacksmiths)

Questions: how many times do they eat meat in a week, and how much? Or alternatively, do they just go without? What do they use to make soup? How much oil or fat do they put in, how much pasta, how many vegetables etc.? How much corn do they grind, and how many loaves of bread do they buy? How much coffee or coffee substitute, how much sugar? How much milk for the children etc.?”

Reversing Gramsci’s questions would mean that I would like to know how many times a week the owners of garment and knitwear factories?those who receive orders, and deliver supplies to Wal-mart, Marks & Spencer, Carrefour, Tesco, JC Penny, H&M, Gap?eat meat, how much oil and butter they consume, how much rice, what quality, how much coffee and beverages they drink, how much they spend on medicine and health, on their childrens education, on holidays, and all other personal and familial needs. I would also like to know how much they contribute, both directly and indirectly, to the election funds of political parties.

At her first court hearing, Mishu had stood in the dock and had asked, `Am I a common criminal that I should have to be handcuffed like this?’

No Mishu, neither you, nor other labour leaders, nor workers demonstrating for living wages, none of you are criminals. Those denying living wages to garment workers, are. It is they who are criminals. Your struggles serve to expose them for what they really are underneath their smooth and slick smiles, their expensive clothes. Petty, miserable, brutal. The real criminals.

Published in New Age, Tuesday December 21, 2010

Support campaign for release of Moshrefa Mishu

Imprisoned, or dead. Reflections on Victory Day, 2010

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

By Rahnuma Ahmed

My heart was heavy on Victory Day.

On Dec 12, four people, including a rickshaw driver aged 35, were killed in Chittagong EPZ as garment workers clashed with police because the new wage structure when implemented, meant getting lesser wages. According to news reports, the management of South Korean-owned Youngone suddenly shut down all its units after workers protested the withdrawal of their Tk 250 lunch allowance. When 10,000 workers turned up for work on Sunday morning, they found the factory closed down for an indefinite period. Demonstrations and picketing took a violent turn when police opened fire with live bullets (600 rounds) and tear gas shells (150 canisters). Workers retaliated with brickbats, sticks and stones. The Deputy Commissioner (Port) in Chittagong claimed, rickshaw-driver Ariful Islam had died from a hurled brick; his employer however said, he had been shot dead. Eight injured persons had bullet wounds. Police filed cases against an unidentified 33,000.

Less than two days later, in the early hours of December 14, a contingent of 12 or so claiming to belong to the Detective Branch, all in plainclothes except 1, turned up at the Kola Bagan house of Moshrefa Mishu, president of Garments Workers Unity Forum. When her sister Jebunnessa wanted to see a warrant, they threatened to arrest her too. Mishu was only allowed to change her clothes, she had to leave her medicine behind: for asthma, and for a severe spinal injury from an attack on her life several years ago. She was produced in court after midday and remanded for 2 days on charges of inciting vandalism during worker unrest in Kuril (Kafrul, Dhaka) in June this year. At the end of 2 days, she was remanded for yet another day. She had Jamaat links, they alleged. It needed further investigation, they said.

Mishu? Remanded? For inciting vandalism? As we sat stunned with this news on the 14th, the gods played a cruel joke.

On December 14, a fire broke out in Ha-Meem Group’s sportswear factory in Ashulia, Dhaka. Fire spread to the dining area on the 10th floor where about 150 workers were having lunch. “Emergency exits were closed,” said Abdul Kader to Asia Times Online. To escape from the rapidly-spreading flames, 50-60 workers jumped off the tenth floor. Many, to their death.

Ha-Meem management says 23 died; hospital and clinic sources report 26 deaths, some newspapers report 31 but workers insist many more as relatives throng at the factory gates in search of missing family members. After being closed for two days to mourn the deaths of workers, it was re-opened on Friday, the weekly holiday, but also, a public holiday due to Ashura. The next day, a large chunk of concrete fell on the floor of the 8th floor, as the devastation caused by the fire was being repaired. Workers rushed out of the building fearing for their lives. At least 25 were injured.

According to the Fire Service and Civil Defence Department, fires broke out in 213 factories between 2006 and 2009. The number of deaths? 414. These figures include the Spectrum/Shahriyar Sweater factory collapse in 2005, when 64 workers were killed and 80 were injured, 54 seriously. It excludes the deaths caused by fire which broke out this February at Garib & Garib Sweater factory, built on marshy land. 21 workers’ died, another 50 were injured.

According to international groups dedicated to improving the working conditions of workers worldwide, the Bangladeshi garment industry is “notorious” for its bad safety record. Most of the deaths and injuries are entirely “preventable.” According to the Clean Clothes Campaign, a global network of labour and women’s rights organisations, Bangladeshi factory owners “blatantly violate building code and health and safety regulations”; the government (regardless of which party is in power) “fails to enforce these regulations.” At Garib & Garib, fire rapidly spread because the floors were filled with inflammable materials such as wool threads, workers who were cut off by the fire could not escape because emergency exits were locked; material piled-high blocked the stairways. Fire brigade officials said, the factory’s fire-fighting equipment was “virtually useless.”

The joke played by the gods was undoubtedly cruel since it snatched away many lives? 23? 26? 31? more??but it pointed fingers as well.

Has any factory owner ever been picked up by the police, remanded, arrested, and charged because of factory fires? Not that I know of. The officer-in-charge of Ashulia thana says, (only) a general diary has been lodged in connection with the fire at Ha-Meem. Interestingly, Ha-Meem Group’s managing director AK Azad is also the president of the Federation of Bangladesh Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FBCCI).

Just as factory fires are not properly investigated, neither are acts of vandalism. One hears ministers, high party officials, intellectuals-serving-party-interests and experts claim every so often that these are caused by `outsiders.’ But these `outside forces’ are never specified. Despite turf wars over waste cloth from the garment industry (jhoot baybsha). Despite cutthroat competition among some of the owners themselves. Despite rumours that some were initiated to claim insurance. Despite competition between exporting nations, too. It is much easier to demonise Mishu, other garment leaders, and workers in general. After all, who knows what Pandora’s box a genuine investigation will open?

Nearly three and half million work in the RMG sector, mostly women. It accounts for 80% of annual export earnings and makes clothes for major Western brands such as Wal-mart, Marks & Spencer, Carrefour, Tesco, JC Penny. In 2006, the monthly minimum wage was fixed at Tk 1,662 (US$23). Since then, despite spiralling prices and soaring living costs, garment workers had received no pay rises, although Bangladeshi labour law dictates that wages should be reassessed and adjusted every three years. The new minimum wage approved in August this year?at 3,000 taka ($43) it fell far short of labour union demands of 5,000 taka ($72)?was grudgingly agreed upon by owners, unwilling to give Eid bonuses according to the new wage structure. Last year, the president of Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) had demanded a 30 billion taka subsidy ($428 million) from the government’s stimulus package fund to pay workers wages and bonuses. It was outrageous even by AL government’s standards which, as Shahidullah Chowdhury, president, Bangladesh Trade Union Centre, points out, is “essentially biased” towards protecting and promoting the interests of the rich. The finance minister rejected it outright, leaving the BGMEA mumbling that it was an “error.”

Clashes occurred in November this year because many factories had either failed to implement what had been agreed upon, or had implemented it through applying a grading system which effectively “lessened” the pay of many workers.

As I write, I remember Mishu telling me many years ago, I seem to be spending my life fighting for basic rights, those that are declared in the ILO Convention, are laid down in Bangladesh law. Struggling for more fundamental changes, for the re-distribution of wealth and resources, is a far cry. These basic rights should be enforced by the government, she said. In its own interest.

Was muktijuddho not fought for ensuring economic and social justice? For changing the lives of the greater majority for the better? The Awami League and its intelligentsia would have us believe that it was fought only against religious forces who had collaborated with the Pakistan government and its army, a sore enough point for the nation given post-1971 events. Given that the war criminals of 1971 were politically restored, given that Jamaat-e-Islami became BNP’s electoral allies, became a part of the government. But the trial of war criminals is a national issue, it should not be subjugated to serve the narrow interests of the Awami League. Nor should we allow it to be capitalised upon by imperial forces, to draw us into the ever-expanding `war on terror.’

The adoption and pursuit of neo-liberal policies have led to the emergence of new forms of femininities in Bangladesh. Women pose, strut down the aisle. The closed-off, vacant look they are trained to wear makes it difficult to tell whether they know that the garments they parade are soaked in sweat. In tears. And, in blood. Of other women.

__________________________________________

Published in New Age, Monday December 20, 2010

Window to the soul

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

A portrait they say, is not so much a likeness of the person being photographed, but a depiction of one?s character. More grand definitions talk of them being a ?window to the soul?. I looked at my portrait of this ?enemy of the country? as a labour minister had declared, and wondered whether I had indeed found a window to her soul. She had just been arrested in Gazipur, and I had no further information.

With numerous cases strategically lodged all over the country on trumped up charges, her arrest was always on the cards. In today?s countrywide strike for workers? pay, facing violent repression, their resistance was a defiant stand for the rights of the oppressed. She and the workers she represented, all knew the risks. She had to lead from the front, come what may.

One is generally kind to bread winners. They are the ones who sit at the head of the table, get the choice piece of meat, make after dinner speeches. Their comfort and their happiness is of prime importance to those who survive on that bread. Bangladesh earns 12 billion dollars from garment exports and gets three quarters of its export earnings from this single sector. One would imagine that the bread winners of Bangladesh, the two million garment workers, mostly women who had migrated from villages in search of work, would be offered a bit more than the Taka 1650 (less than USD 24) per month minimum wage.

But then these enemies of the country, didn?t stop at demanding more than a dollar a day for their work. They wanted weekends off, to be paid overtime, to be paid on time and enjoy statutory holidays. They even objected to their systematized sexual harassment.

So what if the garment sector was the most profitable, and the garment workers amongst the most poorly paid. Some workers getting paid as little as $ 12 a month maybe a bit on the low side, and maternity leave should really be given, but have some sympathy for the owners. Should the BGMEA bigwig owner who bought his wife the expensive Mercedes have to sell his car? It?s not only workers who find Bangladesh a difficult country to live in. The Merc, as I?ve been told, had been expensive to start with. With 850% tax being applied on luxury goods, the poor man had to pay nearly a million dollars for his wife?s set of wheels. OK, so it could have paid for a few $24/month salaries, but then his wife had other costs. They did have standards to maintain.

And these strikes were so annoying. Even in May, the death of the 25?year old worker Rana, led to unrest. The Rapid Action Battalion (RAB)?had to give up its normal task of extrajudicial killings to deal with?workers demanding decent wages.

I just heard that the campaign worked. Mishu?s been released. I should get on with my portraits. Perhaps I should photograph the garment owners to complement the picture of Mishu. Given my earlier failure with portraits, I would need to find the right metaphors for the window to their soul. A chunk of granite, glued to cold steel, wrapped in dollars could perhaps do the trick.

————-

related links: Unheard Voices

A Tribute to Our Forgotten Sisters

Majeda, Jarina, Farida and Many other Garment Workers

By Saydia Gulrukh

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, New York City, March 25, 1911

Whoever saw the hellish fire at 33 Washington Place,

A terrible tragedy, something quite new,

Can never forget it, And everyone knows many lives were lost.

They were incinerated, In a factory 10 stories high.

There were horrible screams from the onlookers,

Those who were burned alive

And those who choked in the smoke.

(Yehuda Horvitz wrote and sung this song to the tune of a Jewish prayer to commemorate?the deaths of Jewish women in the Triangle Fire)

In many ways, the Triangle Shirtwaist Company was just another sweatshop factory?in the heart of Manhattan. It was located on the top three floors of the ten-story Asch Building just at the end of Washington Square. All that characterizes a sweatshop ? low wages, excessively long hours, and unsanitary and dangerous working conditions ? was part of its factory policy. Most of the several hundred Triangle employees were young women.? Many among them were recently-arrived Italian or Jewish immigrants.

On March 25, 1911, as the hours of the clock approached the closing time, a fire broke out on the top floors of the Asch Building. Flames leapt from discarded rags between the first and second rows of cutting tables.? The fire spread everywhere, as several men continued to fling water at the fire.? In the thickening smoke, a shipping clerk dragged a hose in the stairwell into the rapidly heating room, but nothing came out.? Terrified and screaming girls tried to climb down the narrow fire escape.? Some girls trapped on the ninth floor jumped through the window (Leon Stein, Out of the Sweat Shop, 1977). By the time the fire was over, 146 women garment worker had died. The next two days were marked with the horror and grief of families and comrades desperately trying to identify their dear ones from the bodies burned to bare bones.

In 1909, when women garment workers started to organize and called for a strike demanding better pay, safe working environment, Triangle Shirtwaist was one of the factories which agreed to only a partial settlement. One of the demands that was not met in this settlement was the demand for adequate fire escapes (Meredith Tax, The Uprising Thirty Thousands, 1994). These deaths, horrifyingly cruel, agitated the members of International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). Many thousands joined the funeral procession, they mourned the lives lost, and demanded the safety for workers.

Two weeks after the fire, a grand jury indicted Triangle Shirtwaist owners Isaac Harris and Max Blanck on charges of manslaughter. Three years after the fire, on March 11, 1914, twenty-three individual civil suits against the owner of the Asch Building were settled.? The average recovery was $75 per life lost. Calls for justice continued to grow,?thirty-six new laws reforming the state labor code were enacted between 1911 and 1914, those who survived the fire were left to live, and relive, those agonizing moments.

Garib and Garib Sweater Factory, Gazipur, February 25, 2010

21 killed at Garib and Garib Factory, Gazipur, 2010

62 killed at KTS Garments, Chittagong, 2006

23 killed at Shan Knitting, Narayanganj, 2005

23 killed at Chowdhury Knitwear, Narsingdi, 2004

23 killed at Macro Sweater, Dhaka, 2000

12 killed at Globe Knitting, Dhaka, 2000

24 killed at Shanghai Apparels, Dhaka, 1997

20 killed at Jahanara Fashion, Narayanganj, 1997

22 killed at Lusaka Garments, Dhaka, 1996

32 killed at Saraka Garments, Dhaka, 1990

(Source: The Daily Star, March 1, 2010)

It was a little after 9 o?clock at night, workers were finishing their shift. Some were still working, Abdul Mannan of the Garib and Garib factory?s sampling section was among them. He was working on the second floor when he first saw the flame and breathed smoke. It was coming from the first floor. A short circuit had occurred near a large stock of flammable acrylic sweaters, which produced thick and extremely toxic smoke and quickly transformed the factory into a ?gas chamber? (Bdnews24.com, Feb26, 2010). Zarina, Farida, Majeda, Sahara, Majida, Rahima, Shantana, Momtaz, Rasheda, Shahinur, Rawshan, Jahanar, Rina and Sufia were on the sixth floor as the monstrous fire swallowed the building.? The main power was immediately turned off. In the pitch dark, workers, both men and women, ran up stairs to escape, but blazing fires and toxic smoke followed them.

Within half an hour, ambulances and firefighters had circled the building, they started their rescue mission but came across dead bodies only: Kashem, Badal, Alamgir, Mainul and Pradeep, bodies which lay haphazardly in the stairway, there were many others. The events that followed were rather routine. After hours of effort, the fire-fighters tamed the unruly fire.? The Fire Brigade authorities, BGMEA and the government formed three different probe committees to investigate the cause of fire (Daily Star, Feb 27, 2010). In a ?sympathetic? gesture, the authority bore the cost of the burials and kept the factory closed for four days to mourn the deceased workers.? The BGMEA ?expressed sorrow at the death of the workers and announced Tk 2 lakh as compensation for each worker? (New Age, Feb 26, 2010). Labor organizations and left-alliances protested, demanding better compensation, and immediate punishment of those responsible.? They continue to protest, to hold meetings in Muktangon, in Shahid Minar, in Gazipur too, protests which barely manage to prevent us from forgetting about them. Perhaps through taming the fire, the fire-fighters had also tamed the sparks of our anger, anger at the deaths, anger at exploitative and unjust practices in the garments industry.

Collectively Resisting Our Amnesia

The hundred years which separates these two tragedies in the history of the garments industry, incidents that are strikingly similar, also coincides with the international women?s movement which has turned a hundred year’s old. By placing these two stories side by side, I don?t intend to undermine the struggles and achievements of our movement, to argue that ?nothing has changed.? My interest lies in the differences in our response to the two tragedies.

People gathered in thousands to cordon the dead bodies of Triangle factory workers, to hold the hands of hysterically grieving relatives and friends. The ILGWU proposed an official day of mourning. The grief-stricken city gathered in churches, synagogues, and finally, in the streets. In 1911, the funeral procession turned into an ocean of grief as countless numbers of people joined in, while the dead bodies of Zarina, Majeda and Farida were sent in separate ambulances to their village, and the only people who joined in that final journey, besides their family members, were the police. We do not join in their funeral procession in the thousands, we do not take over the street to mourn the lives of these women who had slaved their youth away for the much celebrated, and steady increase in the nation’s GDP. As I read Yehuda Horvitz songs written to commemorate the lives of the women killed in the Triangle fire, I look for songs sung celebrating the lives lost here. What I find is a statistical rhyme, an incomprehensive list of the numbers of workers killed in garments factory fires in the last decade. The thought of garments factories being ?gas-chambers? horrifies us? as long as the news remains fresh, and soon enough, we manage to find ways of returning to the national narrative, working in the garments sector is a stepping stone to women?s empowerment. Images of blazing fires rapidly disappear, stories of Rasheda, Shahinur, Rawshan choking to death are conveniently forgotten. In 1911, many women in the funeral procession in New York city had carried placards which said ?we mourn our loss; we demand real progress in workers protection.? In 2010, we do not mourn our loss. We read of our loss in the newspapers.

There has been much talk of corporate greed and sweatshops, many editorials have been written protesting the criminal indifference of factory owners. Locally and globally, every year thousands of pages are written analyzing the sweatshop economy and the feminization of the global labor force. Perhaps, it’s time to analyze our deadly indifference. On international women?s day, a true tribute to Rahima, Shantana, Momtaz and many other sisters whose names will soon be lost in the statistical crowd, can be offered by resisting our own collective amnesia.

Saydia Gulrukh is a PhD student at the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, USA

and a faculty member of Pathshala, The South Asian Media Academy

Published in New Age, 8 March 2010

Changing their destiny

Letter from Bangladesh

Intro to film: In Search of the Shade of the Banyan Tree ? Shahidul Alam/DrikAV

They all have numbers. Jeans tucked into their high-ankled sneakers. They strut through the airport lounge, moving en masse. We work our way up the corridors leading to the airplane, but many stop just before boarding. The cocky gait has gone. The sad faces look out longingly at the small figures silhouetted on the rooftops. They wave and they wave and they wave. The stewardess has seen it all before and rounds them up, herding them into the aircraft. One by one they disengage themselves, probably realizing for the first time just what they are leaving behind.

Inside the aircraft it is different. They look around at the metallic finish of the interior, try on the headphones and drink lemonade. They have seats together and whisper to each other about each new thing they see. Abdul Malek, sitting opposite me, is in his early twenties. He is from a small village not far from Goalondo. This is his second attempt. He was conned the first time round. This time his family has sold their remaining land as well as the small shop that they part-own. This time, he says, he is going to make it.

As in the case of the others, his had been no ordinary farewell. They had all come from the village to see him off. Last night, as they slept outside the exclusive passenger lounge, they had prayed together. Abdul Malek has few illusions. He realizes that on $110 a month, for 18 months, there is no way he can save enough to replace the money that his family has invested.

But he sees it differently. No-one from his village has ever been abroad. His sisters would get married. His mother would have her roof repaired, and he would be able to find work for others from the village. This trip is not for him alone. His whole family, even his whole village, are going to change their destiny.

That single hope, to change one’s destiny, is what ties all migrants together ? whether they be the Bangladeshis who work in the forests of Malaysia, those like Abdul Malek, who work as unskilled labour in the Middle East, or those that go to the promised lands of the US. Not all of them are poor. Many are skilled and well educated. Still, the possibility of changing one’s destiny is the single driving force that pushes people into precarious journeys all across the globe. They see it not merely as a means for economic freedom, but also as a means for social mobility.

In the 25 years since independence the middle class in Bangladesh has prospered, and many of its members have climbed the social ladder. But except for a very few rags-to-riches stories, the poor have been well and truly entrenched in poverty. They see little hope of ever being able to claw their way out of it, except perhaps through the promise of distant lands.

So it is that hundreds of workers mill around the Kuwait Embassy in Gulshan, the posh part of Dhaka where the wealthy Bangladeshis and the foreigners live. Kuwait has begun recruiting again after the hiatus caused by the Gulf War, and for the many Bangladeshis who left during the War, and those who have been waiting in the wings, the arduous struggle is beginning. False passports, employment agents, attempts to bribe immigration officials, the long uncertain wait.

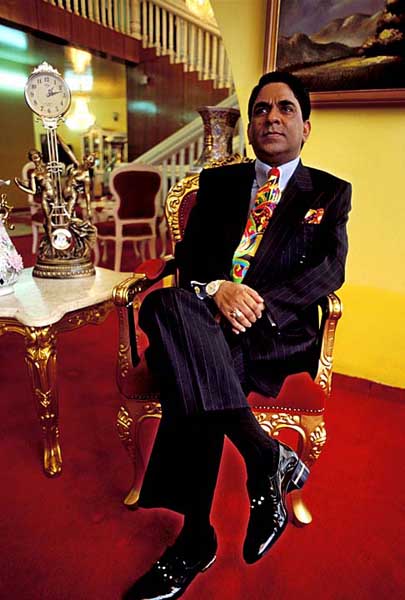

Some wait outside the office of ‘Prince Musa’ in Banani. He is king of the agents. His secretary shows me the giant portraits taken with ‘coloured gels’, in an early Hollywood style. She carefully searches for the admiration in my eyes she has known to expect in others. She brings out the press cuttings: the glowing tributes paid by Forbes, the US magazine for and about the wealthy, the stories of his associations with the jet set. She talks of the culture of the man, his sense of style, his private jet, his place in the world of fashion.

Apart from the sensational eight-million-dollar donation to the British Labour Party in 1994 ? which Labour denies, but which the ‘Prince’ insists was accepted ? there are other stories. Some of these I can verify, like the rosewater used for his bath, and the diamond pendants on his shoes (reportedly worth three million dollars). Others, like his friendship with the Sultan of Brunei, the Saudi Royals and leading Western politicians, are attested to by photographs in family albums.

He was once a young man from a small town in Faridpur, not too distant from Abdul Malek’s home or economic position, who made good. Whether the wealth of the ‘Prince’ derives mainly from commissions paid by thousands of Maleks all over Bangladesh or whether, as many assume, it is from lucrative arms deals, the incongruity of it all remains: the fabulously wealthy are earning from the poorest of the poor.

Whereas the ‘Prince’ has emigrated to the city and saves most of his money abroad, Malek and his friends save every penny and send it to the local bank in their village. Malek is different from the many Bengalis who emigrated to the West after World War Two, when immigration was easier and naturalization laws allowed people to settle. Malek, like his friends, has no illusions about ‘settling’ overseas. He knows only too well his status amongst those who know him only as cheap labour. Bangladesh is clearly, irrevocably, his home. He merely wants a better life for himself than the Bangladeshi princes have reserved for him.

First published in the New Internationalist Magazine

Photo feature on migration

Remaking Destiny

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

www.migrantsoul.org

Who am I? Where do I belong? Who determines my future? Society has no answer to these restless questions. Our sense of identity, kinship and community, are at worst shattered by the experience of migration and at best are thrown into uncertainty.

The universal declaration of human rights talks of a world “without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”. The reality, particularly for the economic migrant, is very different.

Physical, emotional, social and intellectual exclusion reinforce a migrant’s sense of displacement and alienation. The powerful may glide over such barriers, touching down for business, for pleasure or even out of guilt. For those without power, parting is painful, and each barrier crossed, like the ferry ghats of the big rivers, broadens the distance they must travel to return.

Expectations, dreams, duties and needs circumscribe the life of an economic migrant. The single hope, to change one’s destiny, is what ties all migrants together, whether they be the Bangladeshis who work in the forests of Malaysia, the bonded labourers in the sugarcane plantations in India, the construction workers in the Middle East or the hopeful thousands bound for the promised lands of Europe and North America. They see migration not merely as a means to economic freedom, but also as a passport for social mobility. The wealthy can purchase the future they desire. But a migrant who chooses to rewrite an inherited destiny swims against the current and faces the wrath of the gatekeepers who shape that destiny.

Shahidul Alam

Fri Jul 18, 2003