?It?s The Right Thing To Do As A?Country?

By Adrian Carrasquillo on BuzzFeed

Musings by Shahidul Alam

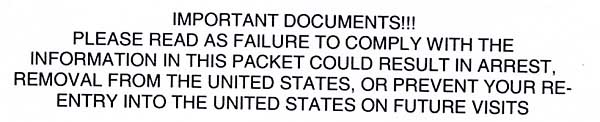

Notice on the welcome pack handed to me as I was taken to the room for “Special Aliens”. JFK Airport. New York. USA

Notice on the welcome pack handed to me as I was taken to the room for “Special Aliens”. JFK Airport. New York. USA

Our leisurely breakfast at Coyoacan was interrupted. ?It?s Trisha,? said Pedro, handing over the phone. I had just come from Dublin where I?d been chatting to Don Mullan about how he came across the incredible information that led to the reopening of the Bloody Sunday enquiry. Conversation veered to Pedro and Trish who had been involved in the project. I was heading for Mexico City. Trisha was not in Mexico but she knew I was visiting Pedro and Nadia in their lovely house in Coyoacan and I was hoping to hear from her. I was conducting the inaugural workshop of the Pedro Meyer Foundation. But Trisha?s call was not just about saying hello. The previous night, she had seen my name in a TV programme in the US. I was on top of a list of ?undesirable professors? who apparently went round the US making extremist speeches. The list included people like Noam Chomsky, so I was in good company, but I wondered where the extremist label had come from.

As it is, I am labelled a ?Special Alien? by US immigration. I generally go to the US at least once a year to speak at the National Geographic. Last year they had also asked me to speak at the PDN (Photo District News) convention at the Jacob Javits Center in New York. Robert Pledge had turned the tables on me and taken advantage of my presence to ask me to speak at the Eugene Smith Award Ceremony at Parson?s School of Design. It was usually I who arm-twisted him into giving time to my students. Every time I arrive in the US, I go through what is now a familiar pattern. I wait in the winding queue at JFK airport. Upon scanning my passport, the immigration officer calls for someone to come over and take me to a separate room. The room, populated mostly by ?not so pale? people, is where ?Special Aliens?? are interrogated.

On my way out, I have to register at the NSEERS (National Security Entry/Exit Registration System) office. This is not always at the terminal I am departing from, so I have to do prior research to ensure I am allowed enough time for this and? don’t miss my plane. I have long stopped expecting to catch a connecting flight in the US, and have informed all my associates accordingly. The immigration officials never explain why I am a ?Special Alien?, and the last time I applied for a visa, the visa officer in Dhaka, who knew my work, had kindly pointed out that I would no longer be subjected to this procedure. I had happily trotted up to immigration on my next visit, knowing I was ?normal? again. But of course it had made no difference. I still ended up in that familiar room. I was asked the same old questions again, and re-fingerprinted and re-photographed for good measure.

Through a link Trish had sent me, I had tried tracing the programme on PBS, but pulled a blank. Rahnuma, who has enough trouble bailing me out (sometimes literally), wasn?t over-excited about this new development. She insisted that I chase it up, and get to the root of the story. She felt sure Brian would be able to dig up the facts. Brian Palmer had turned up many years ago, to do a story on Chobi Mela that Aperture Magazine had commissioned. Last year he had been commissioned by the Pulitzer Foundation to do a film on Pathshala. He had also spoken at Dhaka University of his experience as an embedded journalist in Iraq. His film Full Disclosure had sadly not been completed in time for Chobi Mela V. We had become dear friends over the years. Predictably, it was Brian who came up with the information.

Daniel Pipes on the Fox News show “The O’Reilly Factor” had named M Shahid Alam, an economics professor at Northeastern University, as “unAmerican” for statements he made after 9-11. I don?t know how much lower one?s status can get, but for the moment I was no lower than a ?Special Alien?. As for having a common sir name, well Shahrukh Khan wasn?t bad company!

Rahnuma steadfastly refuses to apply for a US visa, as the application procedure is so humiliating. She finds the UK visa procedure much the same, and has refused invitations to both countries on these grounds. Many friends have left the US and UK because of the hostile environment. My occasional visits, as a speaker at Harvard, UCLA, USC, Stanford and the National Geographic, or even in transit to Latin America does rile me, but I treat it as a useful reminder of what our relationships with these countries are. Friends have found it strange that I refuse to obtain a British passport. The same friends who thought I was foolish in giving up my membership of the colonial Dhaka Club.

I have little liking for queues, but if that is what it takes for me to be separated from these warmongering “tribes”, I?m ready to put up with a bit of waiting. As for my ?Special Alien? status. I wear it as a badge of honour.

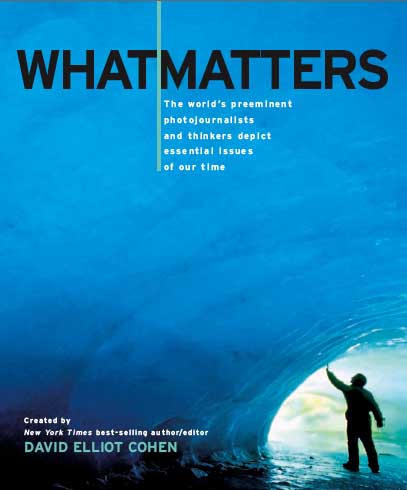

Sterling. 2008. 335p. ed. by David Elliot Cohen. photogs. index. ISBN 978-1-4027-5834-8. $27.95. POL SCI

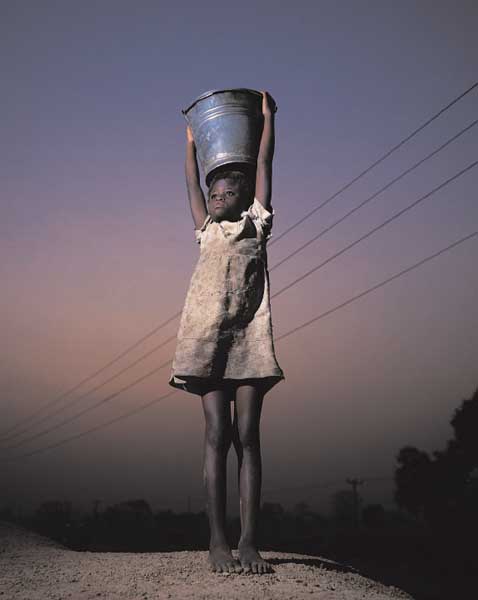

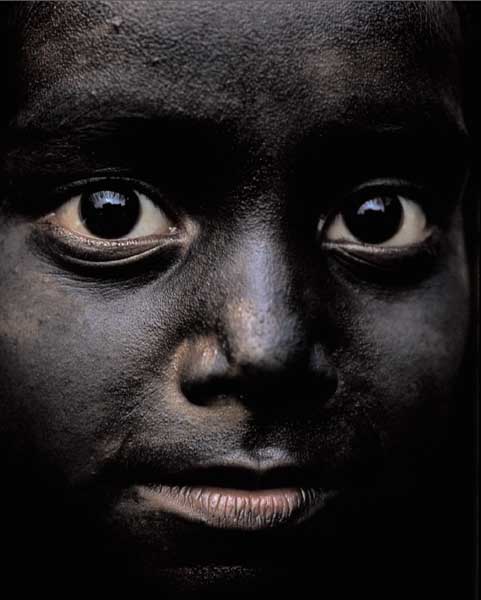

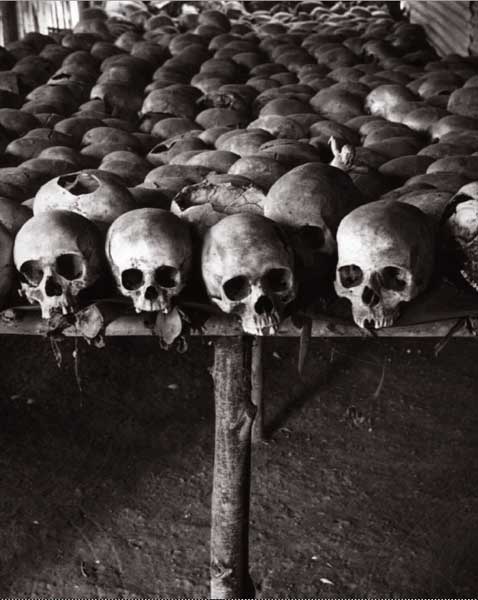

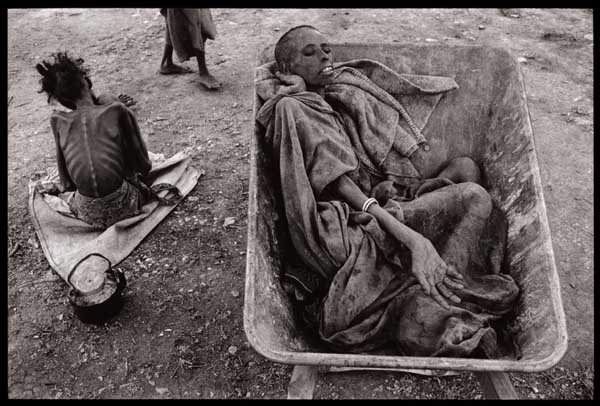

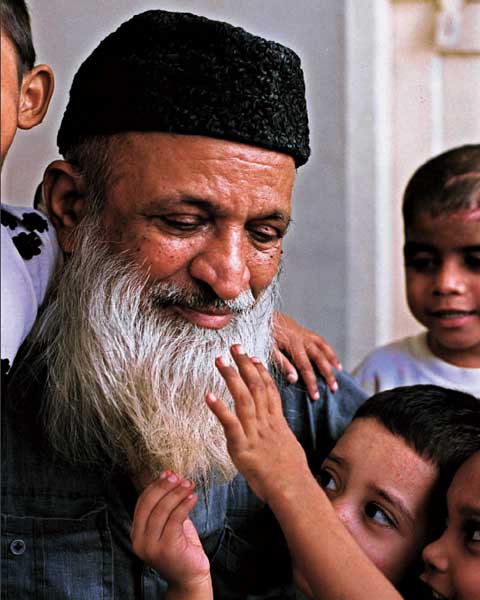

PHOTOGRAPHY EXPOSES TRUTHS, advances the public discourse, and demands action. In What Matters, eighteen important stories by today?s preeminent photojournalists and thinkers poignantly address the big issues of our time?global warming, environmental degradation, AIDS, malaria, the global jihad, genocide in

Darfur, the inequitable distribution of global wealth and others. A “What You Can Do” section offers 193 ways to learn more and get involved.

Shahidul Alam ? The Associated Press ? Gary Braasch ? Marcus Bleasdale ? Raymond Depardon ? Paul Fusco ? Lauren Greenfield ? Maggie Hallahan ? Ed Kashi ? Gerd Ludwig ? Magnum ? Susan Meiselas ? James Nachtwey ? Shehzad Noorani ? Gilles Peress ? Sebasti?o Salgado ? Stephanie Sinclair ? Brent Stirton ? Tom Stoddart ? Anthony Suau ? Stephen Voss

Omer Bartov ? Judith Bruce ? Awa Marie Coll-Seck ? Richard Covington ? Elizabeth C. Economy ? Helen Epstein ? Fawaz A. Gerges ? Peter H. Gleick ? Gary Kamiya ? Paul Knox ? David R. Marples ? Douglas S. Massey ? Bill McKibben ? Samantha Power ? John Prendergast ? Jeffrey D. Sachs ? Juliet B. Schor ?

Michael Watts

What Matters?an audacious undertaking by best-selling editor and author David Elliot Cohen?challenges us to consider how socially conscious photography can spark public discourse, spur reform, and shift the way we think. For 150 years, photographs have not only documented human events, but also changed their course?from Jacob Riis?s expos? of brutal New York tenements to Lewis Hine?s child labor investigations to snapshots of torture at Abu Ghraib prison. In this vein, What Matters presents eighteen powerful stories by this generation?s foremost photojournalists. These stories cover essential issues confronting us and our planet: from climate change and environmental degradation to global jihad, AIDS, and genocide in Darfur to the consequences of the Iraq war, oil addiction, and the inequitable distribution of global wealth. The pictures in What Matters are personal and specific, but still convey universal concepts. These images are rendered even more compelling by trenchant commentary. Cohen asked the foremost writers, thinkers, and experts in their fields to elucidate issues raised by the photographs.

Some stories in What Matters will make you cry; others will make you angry; and that is the intent. What Matters is meant to inspire action. And to facilitate that action, the book includes an extensive ?What You Can Do? section??a menu of resources, web links, and effective actions you can take now.

Cohen hopes What Matters will move people to take positive steps??no matter how small??that will help change the world. As he says in his introduction, the contributors? work is so compelling that ?if we show it to you, you will react with outrage and create an uproar.? If, says Cohen, you look at these stories and think, ?What?s the use? The world is irredeemably screwed up,? we should remember that, historically, outraged citizens have gotten results. ?We did actually abolish slavery and child labor in the US; we abolished apartheid in South Africa; we defeated the Nazis; we pulled out of Vietnam. As the saying goes, ?All great social change seems impossible until it is inevitable.? ?

– Michael Zajakowski, Chicago Tribune

A. Newspapers and Online

1. Hard to see, impossible to turn away – Issues and images combine in ‘What Matters,’ a powerful and passionate new book

“Great documentary photojournalism, squeezed out of mainstream newspapers and magazines in an age of shrinking column inches, has had a hard time gaining traction in other venues… But nobody has told the 18 photographers in “What Matters: The World’s Preeminent Photojournalists and Thinkers Depict Essential Issues of Our Time.” These are photo essays by some of today’s best photojournalists following the great tradition begun over a hundred years ago with the expos?s of New York tenement life by Jacob Riis. Through the doggedness of these photographers?who are clearly committed to stirring us out of complacency?all the power and passion of the medium is evident in this book… Some of the pieces will break your heart, some will anger you. All will make you think. To channel your thoughts and feelings into action, the book ends with an appendix “What You Can Do,” offering hundreds of ways to be a part of the solution to these problems.”

– Chicago Tribune Book Review, 2 page spread

2. “Must viewing.”

– San Francisco Chronicle, 2 page story

3. Photographs that Can Change the World

“David Elliot Cohen?s new book, What Matters, which hits bookshelves today, is a collection of photo essays that explore 18 distinct social issues that define our time. Shot by the world?s most renowned photojournalists, including James Nachtwey, who has contributed to V.F., the photographs explore topics ranging from genocide and global warming to oil addiction and consumerism, offering a raw view into the problems that plague our world. Each photo essay is accompanied by written commentary from an expert on the issue. Cohen hopes the book will inspire people to work toward resolving these problems. ?Great photojournalism changed the world in the past, and it can do it again,? Cohen says. ?I want people to see these images, get angry, and act on that anger. Compelling images by the world?s best photojournalists is the most persuasive language I have to achieve this.?

– vanityfair.com

4. Book Review: What Matters

“Changing the world might sound like a lofty goal for a photo book, but that?s what the new book, What Matters, The World?s Preeminent Photojournalists and Thinkers Depict Essential Issues of our Time edited by David Elliot Cohen (Sterling Publishing, $28, 2008), hopes to do. Citing the power of socially conscious photographers over the last 150 years, the beautiful collection of 18 photo-essays by some of today?s prominent photojournalists hopes to ?inform pre-election debate and inspire direct action.” Regardless of what side of the political fence you sit on, this collection of heartbreaking and powerful stories and images is guaranteed to get you thinking.”

– Popular Photography

5. What Matters: The World’s Preeminent Photojournalists and Thinkers Depict Essential Issues of Our Time.

Those doubting the power of photojournalism to sway opinion and encourage action would do well to spend some time with this book. In 18 stories, each made up of photos by leading photojournalists and elucidated by short essays by public intellectuals and journalists, this book explores environmental devastation, war, disease, and the ravages of both poverty and great wealth. The photos are specific and personal in their subject matter and demonstrate how great photography can illuminate the universal by depicting the specific. Cohen has a goal beyond simply showcasing terrific photography. In his thoughtful introduction, he makes explicit his aim to connect the work compiled here with the great tradition of muckraking photography that helped to change conditions in New York tenements and to end child labor at the turn of the last century. A terrific concluding chapter directs readers to specific actions they can take if they are moved to do so by the book’s images, and it’s hard to imagine the reader who would not be moved. Highly recommended for public libraries and academic libraries supporting journalism and/or photography curricula. (a starred review in Library Journal generally means the book will be acquired by many libraries.)

– Library Journal

6. First of five part series about What Matters

(The first installment drew 500,000 page views)

– CNN.com

7. Second part in CNN. Black Dust by Shehzad Noorani

Hello, it was a woman?s voice. Yes, hello. Is that the post-grad room in Sussex University? Yes, I replied cautiously. Can I speak to Ayesha Imam? Well, no, she hasn?t come in yet. Do you want to leave a message…? Yes, could you please tell her I called, my name is… I am a TV producer. I?ll call again, after lunch, thanks. Okay, sure, I replied.

Ayesha came in late. She was well-known in university feminist circles, and much admired. We shared office space, and the rest of us would often receive phone calls intended for her. A call from Dakar inviting her to a Women Living under Muslim Laws conference. Or a call from Channel Four, inviting her to be a panellist. Keen intelligence, a cutting sense of humour, a Nigerian father and a Chinese mother. Beautiful ancestry, beautiful eyes. I passed on the message to her as soon as she came in. Ayesha frowned. Why, what?s the matter? They want to make a programme on FGM, female genital mutilation in Africa, but, well… how shall I put it… hmm what do I say? Well, what about….

Soon after lunch, the phone rang. I was working at the other end of the room but I could clearly hear this end of the conversation. ?Yes, of course I am very interested, but surely you are not thinking of making a programme on female genital mutilation only. I think there are broader issues involved, I think there?s a core issue, that of female bodily mutilation, and surely that?s a universal phenomenon. It manifests differently in Western societies… I mean, it?s not the same in all cultures, not the same interests everywhere… in some places it?s religion, or customs, somewhere else, there are commercial interests, there?s advertising, and yes also, medical science. The issue is female bodily mutilation, I think that?s how male-centredness is secured in social life. I am sure you are thinking of covering all aspects in your programme, clitoridectomy, infibulation of course all these, but also let?s say, hmm, you know Western practices, like silicone breasts, liposuction, collagen implants in lips? Of course, in choosing these, Western women exercise their freedom, and African women are forced into submission, they have no say etc, etc, but surely we can go beyond these ideas, delve a bit deeper??

A wicked smile hovered on Ayesha?s lips as she told me, ?She didn?t sound enthusiastic today.?

The producer did not get in touch with Ayesha later. Maybe her funding sources had dried up. Maybe she couldn?t get hold of a sponsor. Or maybe she didn?t like the comparison between Middle Eastern/African, and Western women.

This was 1993.

She is American and teaches photography. She had come with her husband and two other friends for dinner, about three weeks ago. As they were leaving, she asked me, ??and when do we get to see you in New York?? I immediately replied, ?In that police state? No, never.? I quickly turned to Shahidul and egged him, ?Go on, tell her about your Special Alien status. Tell her what you went through in your last visits to the US.? Shahidul didn?t need much persuasion. ?There was a long line at the airport, I think this was 2005, they took my fingerprints, my photograph, asked a lot of questions. I was led into another room, a large room with long queues. Latinos, Asians, Africans.? ?Any whites?? I butted in. ?Just a few. When it was finally my turn, more questions. Why had I come? For how many days? Where would I stay? Who would I meet? Had I ever visited America before? How many times? Why? Would I be travelling to other states? Why? I could see that he had all the answers at his fingertips, from the visa form I had filled in at the US embassy in Dhaka. But I guess, they hope to tire you out, so that you slip. They took my fingerprints and photograph again, as if my prints, my face had changed in a matter of hours!

?When I left the States I didn?t know that I?d have to go through the same process. When I entered the US again, on another visit, they looked into their computers and warned me, if you fail to exit properly the next time, you?ll be banned for life. Yes, that?s what they said! And y?see, when you are departing, the NSEERS (National Security Entry-Exit Registration System) room for visitors who are exiting is located somewhere else, it?s not the same room, or even the same terminal. Pretty confusing. And in each airport, it?s some place else. Looking for it is a hassle. I remember missing my flight. I had to go through security check, go out of the building, get registered as a Special Alien, this means questions, fingerprints, photographs, then come in again, into the main airport building. Three security checks, in all. And that?s how it?s been, since then. But it depends on who you get, at one of the airports all the officials were Latino, they were very nice. They had to do their job but they weren?t gung-ho, no, not at all.?

?How can you live there?? I couldn?t help asking her. ?And of course, you must know about these detention centres that are being built, for… what is it called, ?new programmes.? What on earth do they mean? Are they going to put American Muslims into these centres? Like they did with the Japanese Americans during World War Two??

She said, ?Well, nowadays, back home I myself feel like an alien. A Special Alien.?

Of course, Shahidul?s alien-ness has material consequences (fine, deportation), that hers doesn?t. Not that she is to blame. Since 9/11, America?s terrorism policy has been reshaping its immigration policy. Muslims, whether those who intend to live there permanently, or those who enter the US on a temporary basis, ?for tourism, medical treatment, business, temporary work, study or other, similar reasons,? are subjected to greater scrutiny, to a profiling regime. In order to ?safeguard US citizens and America?s borders,? the US government has packed off even foreign nationals to its gulag, the Guantanamo. Even citizens of nations where the US is not an occupying power (Syria, Kuwait, Algeria, UK, Canada, Australia).

To paraphrase Karen C Tumlin?s words (California Law Review), Muslim visitors to America are special suspects first, welcome newcomers second. If at all.

The chief adviser Dr Fakhruddin met the press for the first time on November 14 after taking office on January 11, 2007. He said, ?I don?t think the common people are facing any problems due to continuation of the state of emergency.? (New Age, 15 November 2007)

I love statements like that. Not that I think he was being insincere. He comes across as being pretty genuine, in an earnest sort of way. At times, he does seem a bit perplexed. But then, these are difficult times.

No, I do not doubt his sincerity. It?s not that, it?s something else. When he claims to know how common people are, how does he know? Enveloped and cushioned as he is ? as they are ? by our constitutional rights being suspended, by emergency laws, by joint forces, remands, a muffled media, sycophants, by pats on the back by Western murubbi diplomats, how does he know how common people are? How cyclone Sidr survivors who had demanded relief felt on being interned by the police? What everyday shoppers think when powdered milk prices shoot up by 100 takas within a week? What do those who queue for rice at BDR shops want to do after having inched their way up only to be told that supplies have finished?

Reading what Dr Fakhruddin thinks reminds me of something Patricia Hill Collins, black social theorist, had written. I dig it out. Collins, in her discussion of standpoint theory, had quoted Rosa Wakefield, an elderly domestic worker. Wakefield was assessing how the standpoints of the powerful and those who serve them, like her, diverge. Her words, ?If you eats these dinners and don?t cook ?em, if you wears these clothes and don?t buy or iron them, then you might start thinking that the good fairy or some spirit did all that… Black folks don?t have no time to be thinking like that… But when you don?t have anything else to do, you can think like that. It?s bad for your mind, though.?

Rosa knows.

Letter from Bangladesh

They all have numbers. Jeans tucked into their high-ankled sneakers. They strut through the airport lounge, moving en masse. We work our way up the corridors leading to the airplane, but many stop just before boarding. The cocky gait has gone. The sad faces look out longingly at the small figures silhouetted on the rooftops. They wave and they wave and they wave. The stewardess has seen it all before and rounds them up, herding them into the aircraft. One by one they disengage themselves, probably realizing for the first time just what they are leaving behind.

As in the case of the others, his had been no ordinary farewell. They had all come from the village to see him off. Last night, as they slept outside the exclusive passenger lounge, they had prayed together. Abdul Malek has few illusions. He realizes that on $110 a month, for 18 months, there is no way he can save enough to replace the money that his family has invested.

But he sees it differently. No-one from his village has ever been abroad. His sisters would get married. His mother would have her roof repaired, and he would be able to find work for others from the village. This trip is not for him alone. His whole family, even his whole village, are going to change their destiny.

That single hope, to change one’s destiny, is what ties all migrants together ? whether they be the Bangladeshis who work in the forests of Malaysia, those like Abdul Malek, who work as unskilled labour in the Middle East, or those that go to the promised lands of the US. Not all of them are poor. Many are skilled and well educated. Still, the possibility of changing one’s destiny is the single driving force that pushes people into precarious journeys all across the globe. They see it not merely as a means for economic freedom, but also as a means for social mobility.

In the 25 years since independence the middle class in Bangladesh has prospered, and many of its members have climbed the social ladder. But except for a very few rags-to-riches stories, the poor have been well and truly entrenched in poverty. They see little hope of ever being able to claw their way out of it, except perhaps through the promise of distant lands.

So it is that hundreds of workers mill around the Kuwait Embassy in Gulshan, the posh part of Dhaka where the wealthy Bangladeshis and the foreigners live. Kuwait has begun recruiting again after the hiatus caused by the Gulf War, and for the many Bangladeshis who left during the War, and those who have been waiting in the wings, the arduous struggle is beginning. False passports, employment agents, attempts to bribe immigration officials, the long uncertain wait.

Some wait outside the office of ‘Prince Musa’ in Banani. He is king of the agents. His secretary shows me the giant portraits taken with ‘coloured gels’, in an early Hollywood style. She carefully searches for the admiration in my eyes she has known to expect in others. She brings out the press cuttings: the glowing tributes paid by Forbes, the US magazine for and about the wealthy, the stories of his associations with the jet set. She talks of the culture of the man, his sense of style, his private jet, his place in the world of fashion.

Apart from the sensational eight-million-dollar donation to the British Labour Party in 1994 ? which Labour denies, but which the ‘Prince’ insists was accepted ? there are other stories. Some of these I can verify, like the rosewater used for his bath, and the diamond pendants on his shoes (reportedly worth three million dollars). Others, like his friendship with the Sultan of Brunei, the Saudi Royals and leading Western politicians, are attested to by photographs in family albums.

He was once a young man from a small town in Faridpur, not too distant from Abdul Malek’s home or economic position, who made good. Whether the wealth of the ‘Prince’ derives mainly from commissions paid by thousands of Maleks all over Bangladesh or whether, as many assume, it is from lucrative arms deals, the incongruity of it all remains: the fabulously wealthy are earning from the poorest of the poor.

Whereas the ‘Prince’ has emigrated to the city and saves most of his money abroad, Malek and his friends save every penny and send it to the local bank in their village. Malek is different from the many Bengalis who emigrated to the West after World War Two, when immigration was easier and naturalization laws allowed people to settle. Malek, like his friends, has no illusions about ‘settling’ overseas. He knows only too well his status amongst those who know him only as cheap labour. Bangladesh is clearly, irrevocably, his home. He merely wants a better life for himself than the Bangladeshi princes have reserved for him.

An old friend of the NI, Shahidul Alam is guiding light of Drik, a remarkable photographic agency in Dhaka.