Subscribe to ShahidulNews

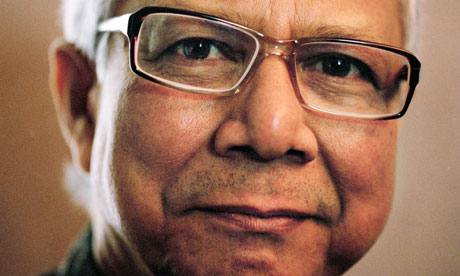

Muhammad Yunus banks on beating the enemies of microfinance

The Nobel peace prize winner discusses recent attacks on his schemes to relieve poverty, from within Bangladesh and abroad

Madeleine Bunting

guardian.co.uk, Monday 18 July 2011 09.43 BST

Muhammad Yunus is good at being calm. At 7.30am in a chilly office in central London, he talks with urbane charm and all the dispassionate objectivity of a philosopher as he considers the Bangladeshi government’s campaign against him, and the possibility that it might destroy his life’s work building up the world’s first microfinance bank.

He is Bangladesh’s most famous son, known as the world’s banker to the poor, winner in 2006 with the Grameen Bank of the Nobel peace prize, a tireless campaigner at global summits for microfinance and social enterprise who can count Hillary Clinton, Nicolas Sarkozy and Mary Robinson among his many friends. But as the saying goes, a prophet is never recognised in his own country. Neither the global acclaim ? nor the protestations of both the French and the US government ? is making much difference to a government intent on destroying Yunus’s hold on Grameen Bank and the network of social enterprise companies he has developed over the last four decades.

Bangladesh’s prime minister, Sheikh Hasina Wajed has accused him of “sucking blood from the poor”, and others have alleged corruption despite official government inquiries clearing him last month of any wrongdoing. In the end, the only charge that has stuck is that at a sprightly 70, he is too old to be managing director of the Grameen Bank. A charge made, incidentally, by the 77-year-old finance minister.

“I’m not hurt by the vilification in the press; I’m disappointed and I’m worried. I don’t want to see an organisation which has come all this way and brought so much good to the country and brought power to the people, come to this. Many people are angry but anger doesn’t solve anything,” he says.

“I want to calm things down. If we are prepared, we can do damage control.”

This is his first interview since the crisis broke early this year. Yunus is refusing to talk to the Bangladeshi media for fear of further inflaming the controversy, and he is adamant that he will not be drawn into speculating as to why the government has forced his recent resignation. He simply says: “I can’t see the purpose, I can’t see what the country gains, what the government gains.”

There is certainly a lot to lose. Any bank depends on confidence and the last few months have been turbulent for Grameen’s 22,000 employees and 8.36 million borrowers, 97% of whom are women. So far, repayment rates on the millions of small loans are holding steady and borrowers are not withdrawing deposits ? either could bring the bank to collapse. Yunus’s calmness in London is all about steadying the confidence of his Bangladeshi audience. As one of the most efficient and stable economic institutions in a desperately poor country, there are many who are hoping he will succeed and that Grameen will weather this storm.

It was a YouTube version of a documentary film made by a Dane and broadcast in Norway late last year about Yunus, Grameen Bank and microfinance generally that prompted the outcry against him. The film ? in Norwegian, it has not yet been translated ? eventually prompted a government review of the Grameen Bank, investigating a number of charges ranging from some obscure accounting between Grameen subsidiaries and the Norwegian aid agency in the 1990s, to the charging of high interest rates to poor borrowers.

The government review cleared Yunus in April, but made a number of recommendations for the future of the Grameen Bank. At the same time, the government followed another line of attack with the finance minister ordering that he resign because he is too old; Grameen Bank took the minister to court and lost. Reluctantly, Yunus decided that to avoid further turbulence, he had no option but to resign. He is hoping that “good sense will prevail” and the government will allow him to take up a position of non-executive chair to oversee the transition.

While Yunus refuses to be drawn on the reasons for this bitter political dogfight, his many friends and allies are rushing to his help. An international campaign, Friends of the Grameen, was launched in March, chaired by Mary Robinson, while both the US and the French governments have remonstrated with the Bangladeshi authorities. Clinton phoned to offer her personal support; Nicolas Sarkozy wrote to assure Yunus of his. It’s all a far cry from the day he stood up in Oslo and talked of putting “poverty into a museum” in his Nobel prize acceptance speech.

The most likely explanation for the attacks on him is that Yunus’s brief foray into politics in 2007 unnerved Sheikh Hasina. He announced he was going to set up a political party but ended up abandoning his the idea after only two months. His huge global reputation and the economic weight of the Grameen brand has made enemies insecure.

Yunus may be suddenly unemployed, but he is not short of offers. There has been plenty of interest from all over the world, he admits, adding that he has been offered institutes to head, initiatives to lead, figurehead positions. But on this he is very clear: he is not leaving Bangladesh.

If the man is under siege, so is the idea he nurtured. There is a crisis in the microfinance sector in India, where high rates of interest in the private sector microfinance banks were linked with suicides. Yunus is defiant about microfinance, which he still passionately believes has been of benefit to millions.

“We never said microfinance was a silver bullet,” he insists. “Or why would I bother to create 50 other companies ranging from agriculture to telecommunications? Job creation is the solution to poverty. Loans should only be given to fund enterprises. They mustn’t ever be used for ‘consumption smoothing’ or how can people pay back the loans? It has to be about income generation.”

“When microfinance spread across the world, some people abused it. Some went berserk. In my opinion, if there is any personal profit involved, it should not be called microfinance, which should be totally devoted to the benefit of poor people. People used the respect for microfinance. In every country where there was microfinance they needed proper regulatory authorities to oversee the sector and legislation to define it. I knew that the sector was crippled by an inadequate legal framework.”

Yunus recognises there was some “overbilling” of microfinance, but sees that as part of the way you win donors’ interest in a project. He certainly used powerful rhetoric to urge on efforts in tackling poverty. But beyond that he is unapologetic. He didn’t oversell it; when he talked of putting poverty in a museum it was a “hope”, he says, it was not a plan. And he is emphatic: “Microfinance does reduce poverty. Look at the people who have joined Grameen. It’s the most intensively researched organisation in the world.”

The research in Bangladesh has been positive but then the country’s economy has been growing at 8% a year, and the research has not been rigorous enough to separate out which has been responsible for poverty reduction. Yunus knows these debates about evidence but he will give them no quarter, and he simply repeats: “I believe it reduces poverty; it’s become the fashion to be negative about Grameen.”

“It was the media who built up microfinance,” he says.

On one thing even critics of microfinance agree. Whatever the problems now bedevilling the sector, its originator is being treated appallingly in Bangladesh. As for Yunus, he stoically insists his work must go on. He spends as much time talking about social business now as he does about microfinance, such as developing partnerships with businesses such as the food company Danone to create enterprise schemes for the poor. Institutes dedicated to social business have recently been launched in Glasgow and Paris.

“I’m programmed to keep working,” he smiles, and then he allows himself a little self-aggrandisement. “It’s like Socrates or Galileo. If you are saying something different or new, and it doesn’t fit, it will create tension. If people applaud, you’re not doing something new. If people get shocked, you’re in business.”