by Rahnuma Ahmed

`Still pictures are not still…’ said Mahasweta Devi. She was in Dhaka to inaugurate Chobi Mela V, and, fortunately for us, had expressed her wish to put up with Shahidul Alam, the director of Chobi Mela. Having Mahasweta Devi, and Joy Bhadra, a young writer and her companion, as house guests, was a `happening’. I will write about that another day.

Mahasweta Devi consistently used the words stheer chitro (exact translation is, `still images’). Still pictures, she went on, inspire us. They move us. They make us do things.

However, I thought to myself, many who are working on visual and cultural theory may not agree. Some would be likely to say, things are not as simple as that.

The effect of visual images needs to be investigated

The debate about the power of visual images has become stuck on the point of the meaning of visual images, on the truth of images. This, said David Campbell, a professor of cultural and political geography, doesn’t get us very far. He was one of the panelists at the opening night’s discussion of Chobi Mela V, held at the Goethe Institut auditorium (`Engaging with photography from outside: An informal discussion between a geographer, an editor and a curator/funder of photography’, 30 Jan 2009).

[wpvideo VpfQJKdX]

David went on, it is much better to focus on the effect of images, on the function of images, on the work that images do — and that, is how the debate should be framed. At present, attention is overly-focused on the single image, and what we expect of the single image. By doing this we have invested it with too much possibility, we place too much hope on it’s ability to bring about social change. The effect of visual images needs to be investigated, rather than assumed.

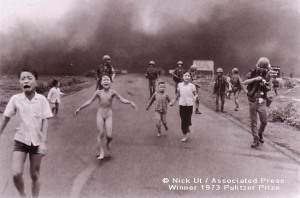

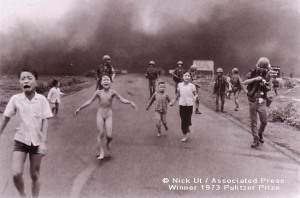

Amy Yenkin, another panelist in the programme, and head of the Documentary Photography project at the Open Society Institute asked David, Why do you think this happens? Is it because people look back at certain iconic images, let’s say images from the Vietnam war that changed the situation, that they try to put too much meaning in the power of one single image..? David replied, `In a way, I am sceptical of the power of single images, a standard 6 or 7 in the western world, that are repeated all the time. I was personally affected by the Vietnam war images, by the image of the young Vietnamese girl fleeing from a napalm bomb, but I don’t know of any argument that actually demonstrates that Nick Ut’s photograph demonstrably furthered the Vietnam anti-war movement.’ He went on, `Now, I don’t regard that as a failure of the image, but a failure of the interpretation that we’ve placed on the image. It puts too much burden on the image itself.’

The discussion was followed by Noam Chomsky and Mahasweta Devi’s video-conference discussion on Freedom (Chobi Mela V’s theme), and I became fully immersed in watching two of the foremost public intellectual/activists of today talk about the meanings and struggles of freedom, and of imperialism and nationalism’s attempts to thwart it in common peoples’ lives.

But the next day, my thoughts returned to what David had said, and to the general discussion that had followed. On David’s website, I came across how he understands photography, `a technology through which the world is visually performed,’ and a gist of his theoretical argument. I quote: `The pictures that the technology of photography produces are neither isolated nor discrete objects. They have to be understood as being part of networks of materials, technologies, institutions, markets, social spaces, emotions, cultural histories and political contexts. The meaning of photographs derives from the intersection of these multiple features rather than just the form and content of particular pictures.’ .

In other words, to understand what happens within the frame, we need to go outside the frame.

Abu Ghraib photographs: concealing more than they reveal

A good instance is provided by the Abu Ghraib prison torture and abuse photographs taken by US military prison guards with digital cameras, which came to public attention in early 2004. The pictures, says Ian Buruma, conceal more than they reveal. By telling one story, they hide a bigger story.

Images of Chuck Graner, Ivan Frederick and the others as “gloating thugs” helped single out, and fix, low-ranking reservist soldiers as the bad apples. As President Bush intoned, it was “disgraceful conduct by a few American troops who dishonoured our country and disregarded our values”. None of the officers were tried, though several received administrative punishment. As a matter of fact, the Final Report of the Independent Panel to Review Department of Defense Detention Operations specifically absolved senior U.S. military and political leadership from direct culpability. Some even received promotions (Maj. Gen. Walter Wodjakowski, Col. Marc Warren, Maj. Gen. Barbara Fast).

The gloating digital images, no doubt embarassing for the US administration, probably helped “far greater embarrassments from emerging into public view.” They made “the lawyers, bureaucrats, and politicians who made, or rather unmade, the rules?William J. Haynes, Alberto Gonzales, David S. Addington, Jay Bybee, John Yoo, Douglas J. Feith, Donald Rumsfeld, and Dick Cheney?look almost respectable.?

But there is another aspect to the story of concealing-and-revealing. Public preoccupation with Abu Ghraib pornography deflected attention from the “torturing and the killing that was never recorded on film,” and from finding out who “the actual killers” were. By singling out those visible in the pictures as the “rogues” responsible, it concealed the bigger reality. That the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib, as Philip Gourevitch and Errol Morris point out, “was de facto United States policy.”

Lynndie England, who held the rank of Specialist while serving in Iraq, expressed it best I think, when she said, ?I didn?t make the war. I can?t end the war. I mean, photographs can?t just make or change a war.?

True. Photographs can?t just make or change a war. But surely they do something, or else, why censor images of the recent slaughter in Gaza? To put it more precisely, surely, those who are powerful (western politicians, journalists, arms manufacturers, defence analysts, all deeply embedded in the Zionist Curtain, one that has replaced the older Iron Curtain) apprehend that the visual images of Gaza will do something? That they will, in all probability, have a social effect upon western audiences? And therefore, these must be acted upon i.e., their circulation and distribution must be prevented.

At times, their apprehension seems to move even further. Images-not-yet-taken are prevented from being taken. Probable social effects of unborn images are foreseen, and aborted.

Censoring Gaza images, for what they reveal

All of this happened in the case of Gaza. But before turning to that, I would like to add a small note on the notion of probability. I am inclined to think that it’ll help to deepen our understanding of the politics of visual images.

As the organisers of a Michigan university conference on English literature remind us (“Fictional Selves: On the (im)Probability of Character”, April 2002), the notion of probability went through a major conceptual shift with the emergence of modernity. What in the seventeenth century had meant “the capability of being proven absolutely true or false” as in the case of deductive theorem in logic, gradually altered in meaning as practitioners searched for rhetorical consensus, and the repeatability of experimental results, leading to its present-day meaning: “a likelihood of occurring.”

What might have occured if Israel had allowed journalists into Gaza? What might have occurred if the BBC instead of hiding under the pretence of “impartiality” had agreed to air the Disasters Emergency Committee’s Gaza Aid Appeal aimed at raising humanitarian aid for (occupied and beseiged) Gazans? What might have occurred if USA’s largest satellite television subscription service DIRECTV had gone ahead and aired the US Campaign to End the Israeli Occupation of Palestine’s `Gaza Strip TV Ad‘?

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WI-ke-0HnuY&color1=0xb1b1b1&color2=0xcfcfcf&hl=en&feature=player_embedded&fs=1]

Could pictures of Israel’s 22 day carnage in Gaza, which killed more than 1,300 Palestinians, have sown doubts in western minds about the Israeli claim of targeting only Hamas, and not civilians? Could photos of bombed UN buildings, mosques, schools, a university, of hospitals in ruins, ambulances destroyed, of dismembered limbs and destroyed factories have forced BBC’s viewers to question whether both sides are to blame? Could pictures of the apartheid wall, the security zone, the checkpoints controlling entry of food, trade, medicine (for over two years) make suspect the Israeli claim that it had withdrawn from Gaza? Could photos depicting the effects of mysterious armaments that have burned their way down into people’s flesh, eaten their skin and tissue away, have given western viewers pause for thought? Could the little story of Israel acting only in self-defense, begin to unravel? Could pictures of Gaza in ruins have led American viewers to wonder whether there is a bigger story out there, and could it then lead them to ask why their taxes are being spent in footing Israel’s military bill (the fourth largest army in the world), to ask why they should continue to sponsor this parasitical state, even when its own economy is in ruins?

May be.

After all, as Mahasweta Devi had said, still pictures are not still. Still pictures (may) move us. They (may) make us do things. The powerful, know this.

—————-

First published in New Age on Monday 16th February 2009

![]()

La Mohammed Kalay, Afghanistan, 2010.

La Mohammed Kalay, Afghanistan, 2010. Abu Ghraib, Iraq, 2003.

Abu Ghraib, Iraq, 2003. Soldiers rest just after the My Lai massacre, 1968.

Soldiers rest just after the My Lai massacre, 1968. My Lai 4, Vietnam, 1968.

My Lai 4, Vietnam, 1968.